Deeply understand how tokenizers work, learning about the BPE algorithm, the tokenization strategies of the GPT series, and implementation details of SentencePiece.

History of LLM Evolution (6): Unveiling the Mystery of Tokenizers

The Tokenizer is a vital yet often overlooked component of LLMs. In our previous language models, tokenization was character-level, creating an embedding table for all 65 possible characters. In practice, modern language models use more sophisticated schemes, operating at the chunk level using algorithms like Byte Pair Encoding (BPE).

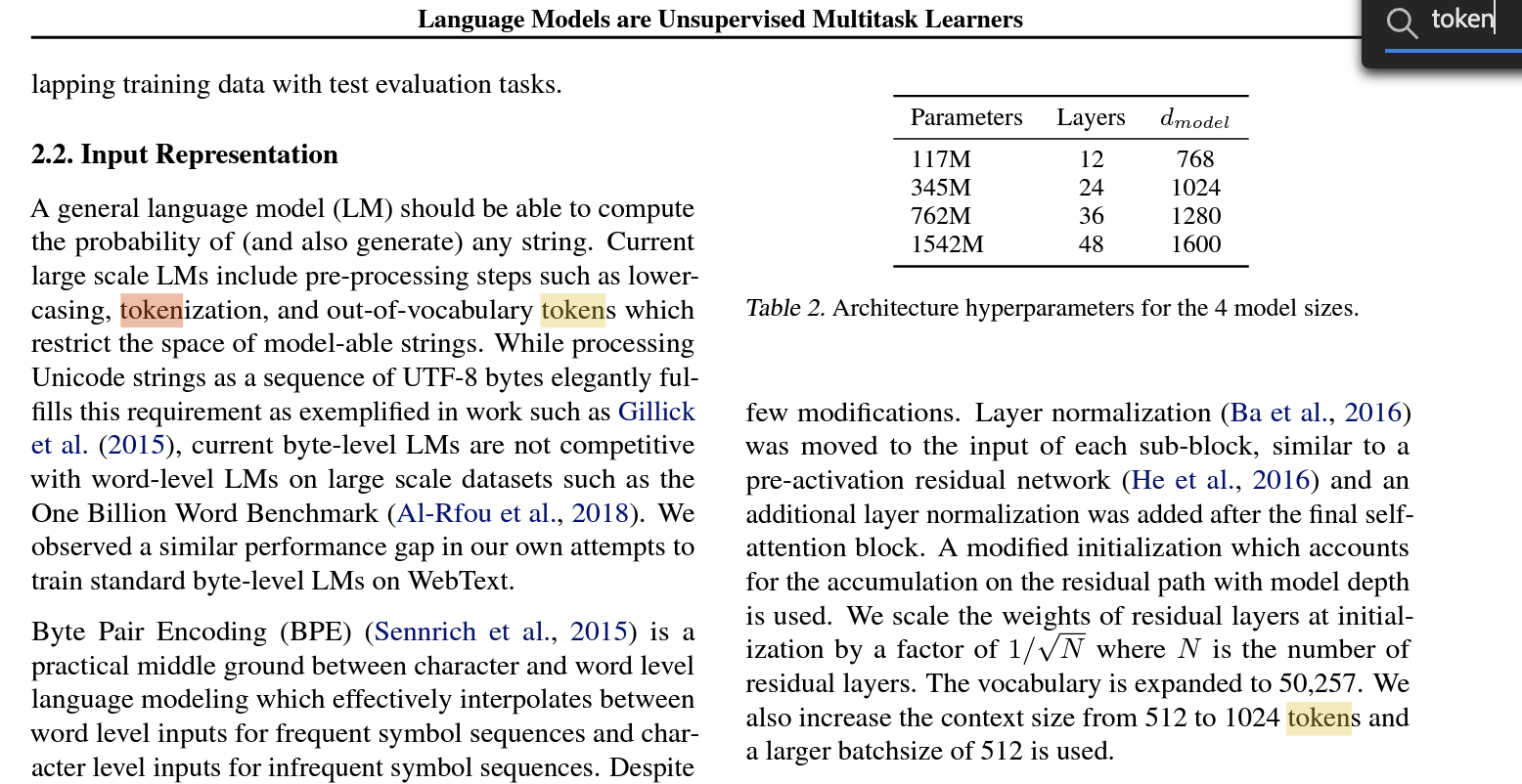

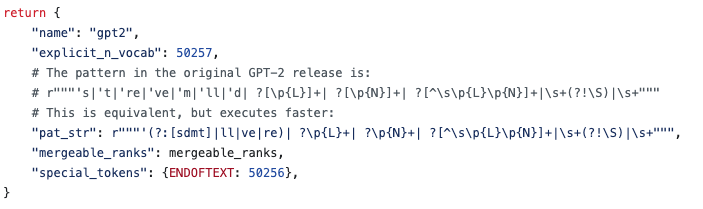

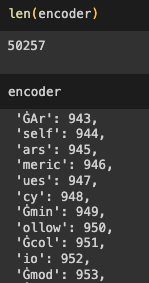

For instance, in the GPT-2 paper Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners, researchers built a vocabulary of 50,257 tokens with a context length of 1024 tokens.

In the Transformer network’s attention layers, each token attends to the preceding 1024 tokens.

Tokens are the atomic units of a language model, and tokenization is the process of converting raw text strings into token sequences.

Side note: Some research (like MegaByte) explores inputting bytes directly without tokenization, though this is not yet fully proven.

First Taste

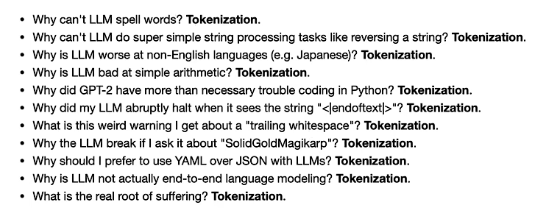

Tokenization is the root cause of many peculiar LLM behaviors:

- Why can’t LLMs spell correctly? Tokenization.

- Why do LLMs struggle with simple string tasks like reversal? Tokenization.

- Why is LLM performance worse for non-English languages (e.g., Japanese)? Tokenization.

- Why do LLMs struggle with simple arithmetic? Tokenization.

- Why did GPT-2 have unnecessary trouble with Python coding? Tokenization.

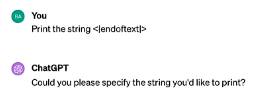

- Why does my LLM stop abruptly when it sees ”<|endoftext|>“. Tokenization.

- What’s with the weird “trailing space” warnings? Tokenization.

- Why does my LLM output nonsense for “SolidGoldMagikarp”? Tokenization.

- Why should I prefer YAML over JSON with LLMs? Tokenization.

- Why aren’t LLMs actually end-to-end language models? Tokenization.

- What is the true source of suffering? Tokenization.

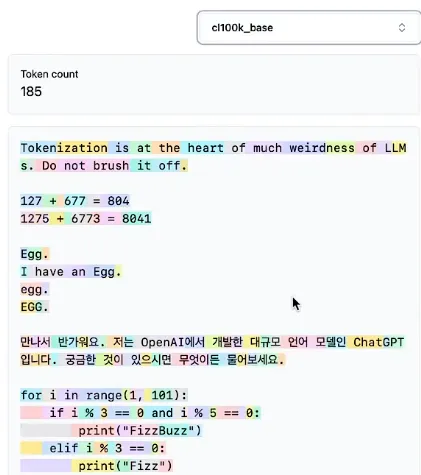

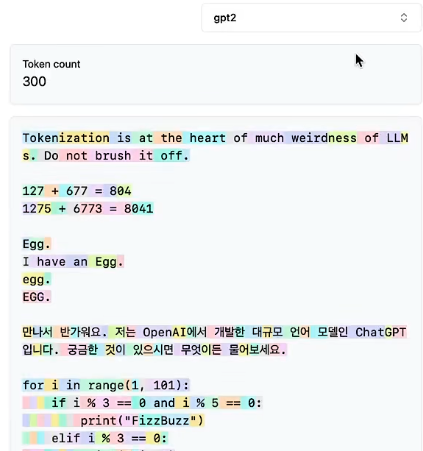

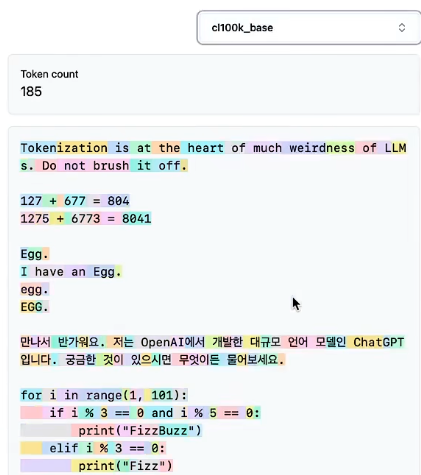

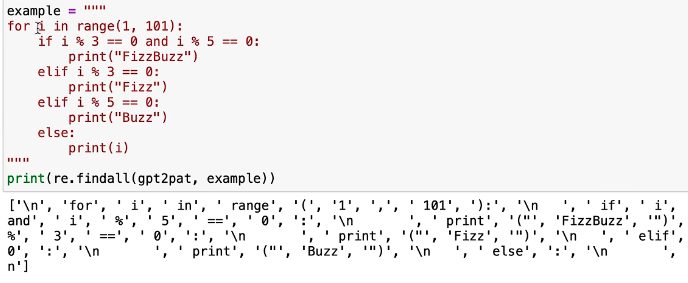

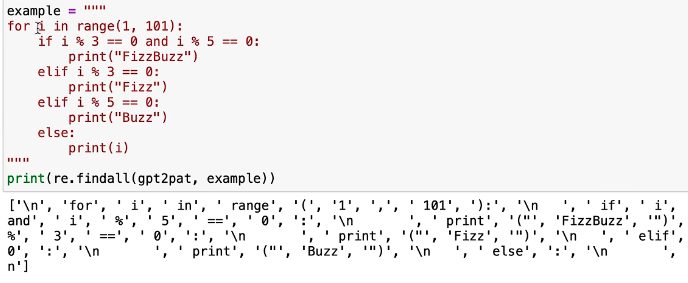

tiktokenizer.vercel.app provides visual tokenization. Let’s look at GPT-2:

Notice that a token often includes the preceding space.

English tokenization looks reasonable. However, in arithmetic, a single number might be split across two tokens. Case sensitivity affects tokenization. Non-English languages are wasteful, often one token per character. In Python, indentation consists of many space tokens, consuming context length. It’s as if non-English sequences are stretched relative to their meaning.

GPT-2’s poor Python performance wasn’t a model issue but a tokenization characteristic.

GPT-4’s tokenizer is much more “reasonable,” especially with whitespace. This intentional choice significantly contributed to GPT-4’s superior coding ability.

GPT-4 consumes nearly half the tokens for the same input, largely because its vocabulary doubled (~50k to 100k).

This compactness is beneficial as it roughly doubles the effective context length for the Transformer. However, increasing the embedding table size increases the cost of the final Softmax. We must balance compactness with computational efficiency.

Unicode

To feed strings into a neural network, we first tokenize them into integer sequences. These integers retrieve vectors from a lookup table for the Transformer input.

How do we support multiple languages and emojis?

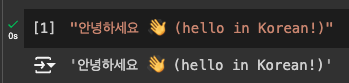

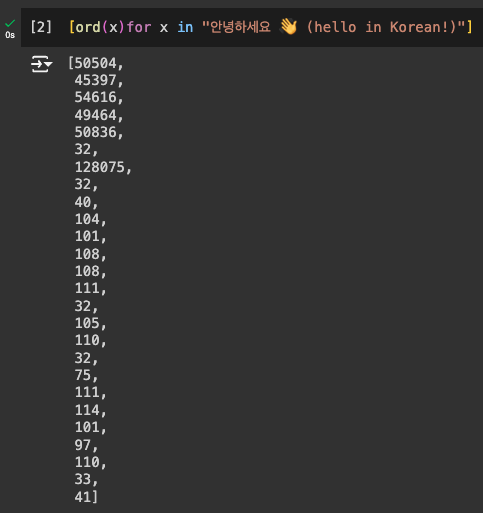

In Python 3, all strings are Unicode strings, supporting characters, symbols, and emojis across languages without encoding worries:

Use

ord()to get Unicode codepoints for characters.

Why not use these codepoints directly as inputs?

One reason is the massive vocabulary (~150,000). Another is that the Unicode standard evolves; we want stability.

UTF-8

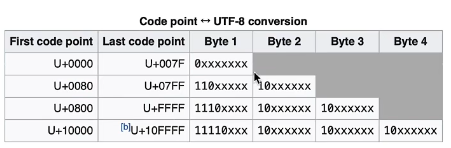

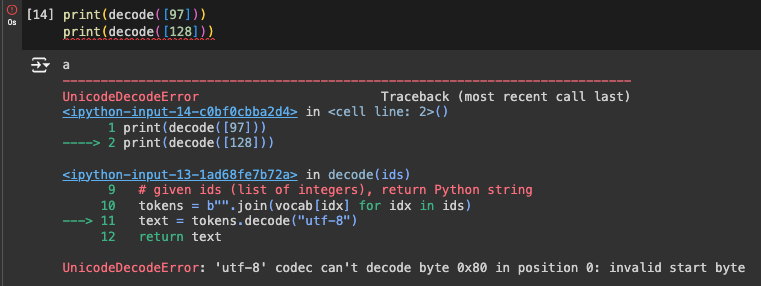

The Unicode Consortium defined UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32. These convert Unicode text into binary data or byte streams. UTF-8 is the most common variable-length encoding.

UTF-8 maps each codepoint to 1-4 bytes. UTF-32 is fixed-length.

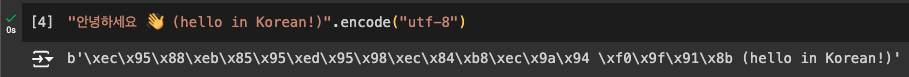

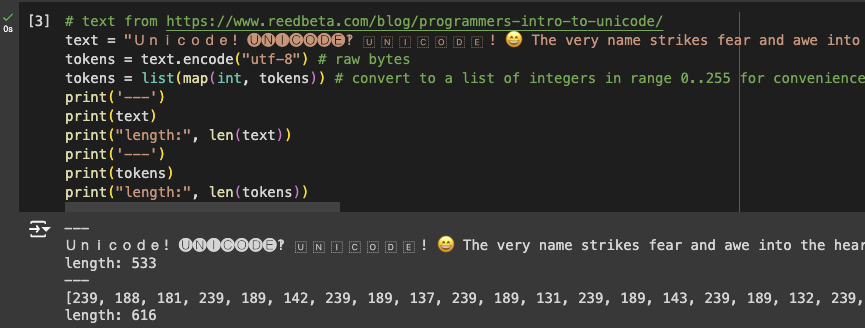

Python strings have an encode method:

:::div{style=“max-width: 500px”}

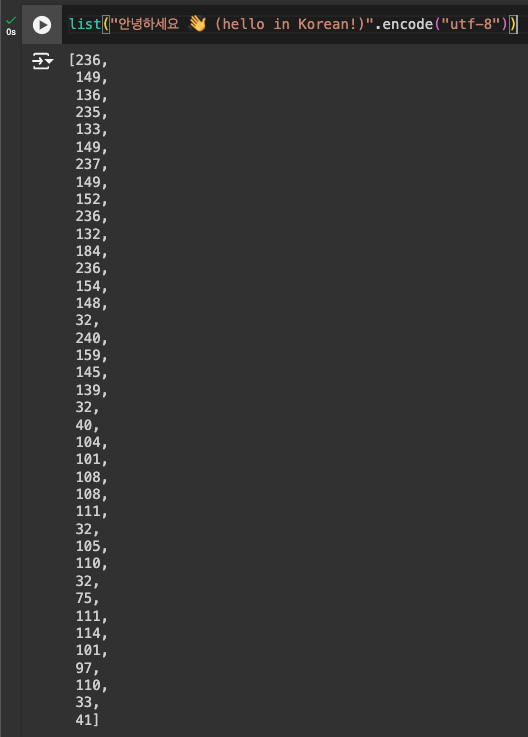

This yields a bytes object. Converting to a list reveals the raw bytes:

:::div{style=“max-width: 100px”}

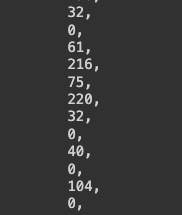

UTF-16 and UTF-32 are wasteful for simple ASCII/English, padding with many ‘0’ bytes:

Directly using raw UTF-8 bytes limits the vocabulary to 256, resulting in excessively long sequences. While this keeps the embedding table small, it’s highly inefficient for Transformers due to limited attention context.

We don’t want raw bytes. We want a larger, adjustable vocabulary built on top of UTF-8.

Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE)

BPE compresses byte sequences into variable amounts. It’s straightforward:

Given:

aaabbdaaaabac

Vocabulary size is 4, length 11 bytes. “aa” is most frequent; replace it with an unused byte like “Z”:

Zabdzabac

Z=aa

Next, replace “ab” with “Y”:

ZYdZYac

Y=ab

Z=aa

Finally, replace “ZY” with “X”:

XdXac

X=ZY

Y=ab

Z=aa

No more pairs occur more than once. Length is now 5, vocabulary size 7.

Unicode characters (like emojis) take multiple bytes in UTF-8, so the initial sequence can be long.

Python implementation:

def get_stats(ids):

counts = {}

for pair in zip(ids, ids[1:]): # Pythonic consecutive iteration

counts[pair] = counts.get(pair, 0) + 1

return counts

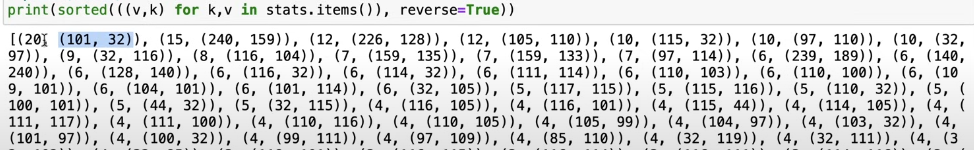

stats = get_stats(tokens)

Sorted byte pair frequencies.

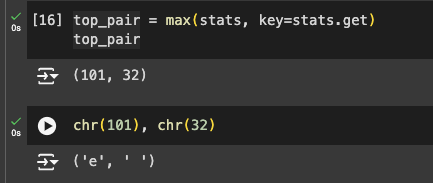

Use chr() to see the characters for the top pair:

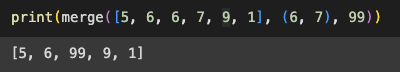

Implementing the merge (minting a new token):

def merge(ids, pair, idx):

# Replace all consecutive occurrences of pair with new token idx

newids = []

i = 0

while i < len(ids):

if i < len(ids) - 1 and ids[i] == pair[0] and ids[i+1] == pair[1]:

newids.append(idx)

i += 2

else:

newids.append(ids[i])

i += 1

return newids

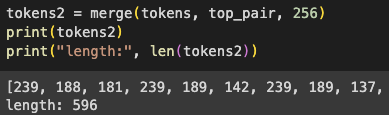

Running on full tokens:

Sequence reduced by 20 bytes (616 to 596).

Iterating this shrinks sequence length but grows vocabulary size. This iteration count is a hyperparameter.

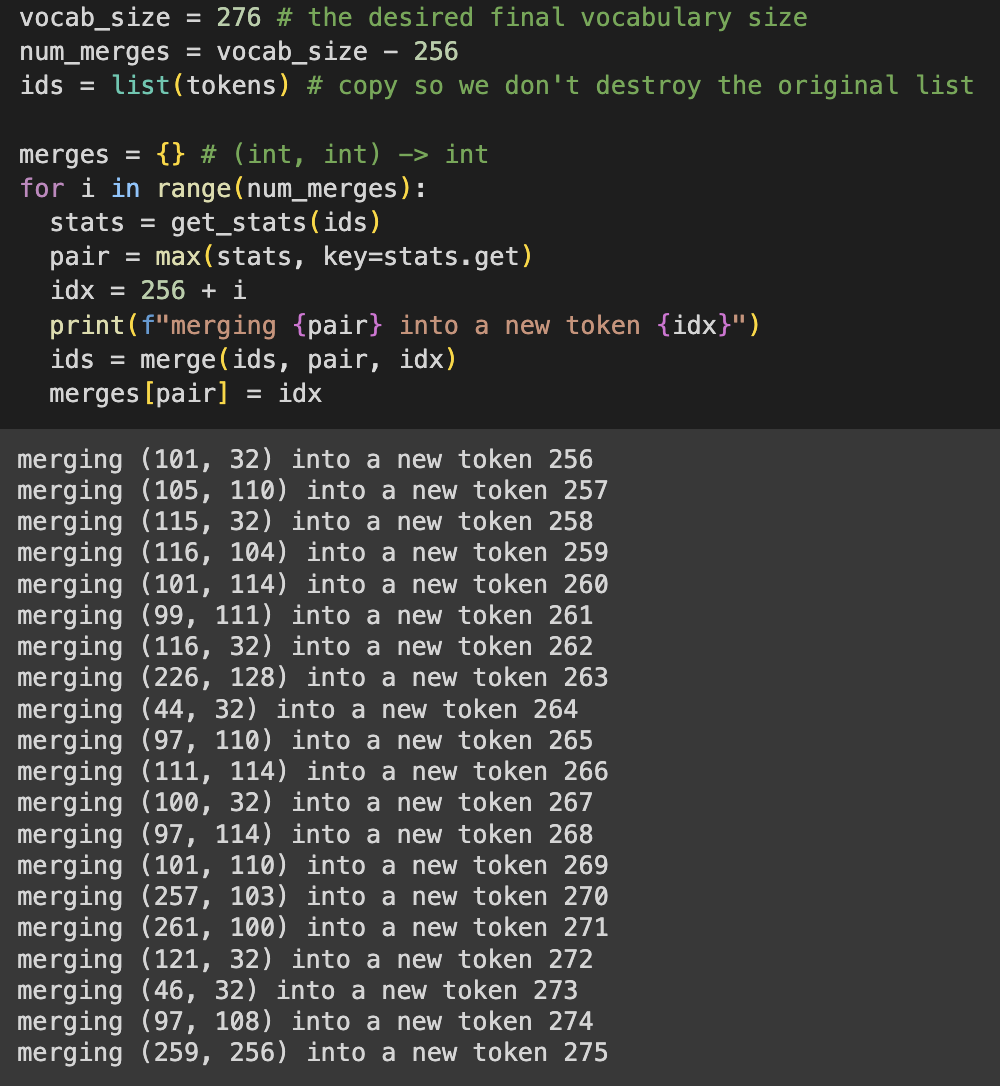

Setting vocab size to 276 (256 + 20 iterations):

New tokens can themselves be merged, building a binary forest.

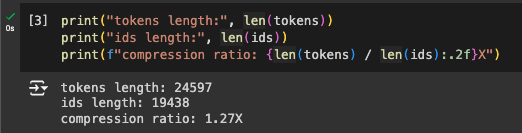

Final compression ratio:

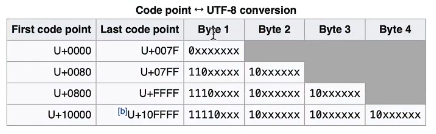

Decode

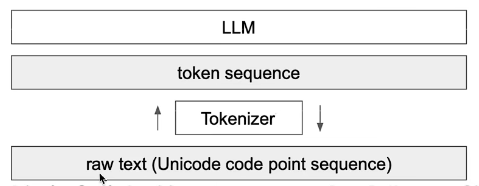

The Tokenizer is a pre-processing stage independent of the LLM, with its own training set. It acts as a translation layer between raw text and token sequences:

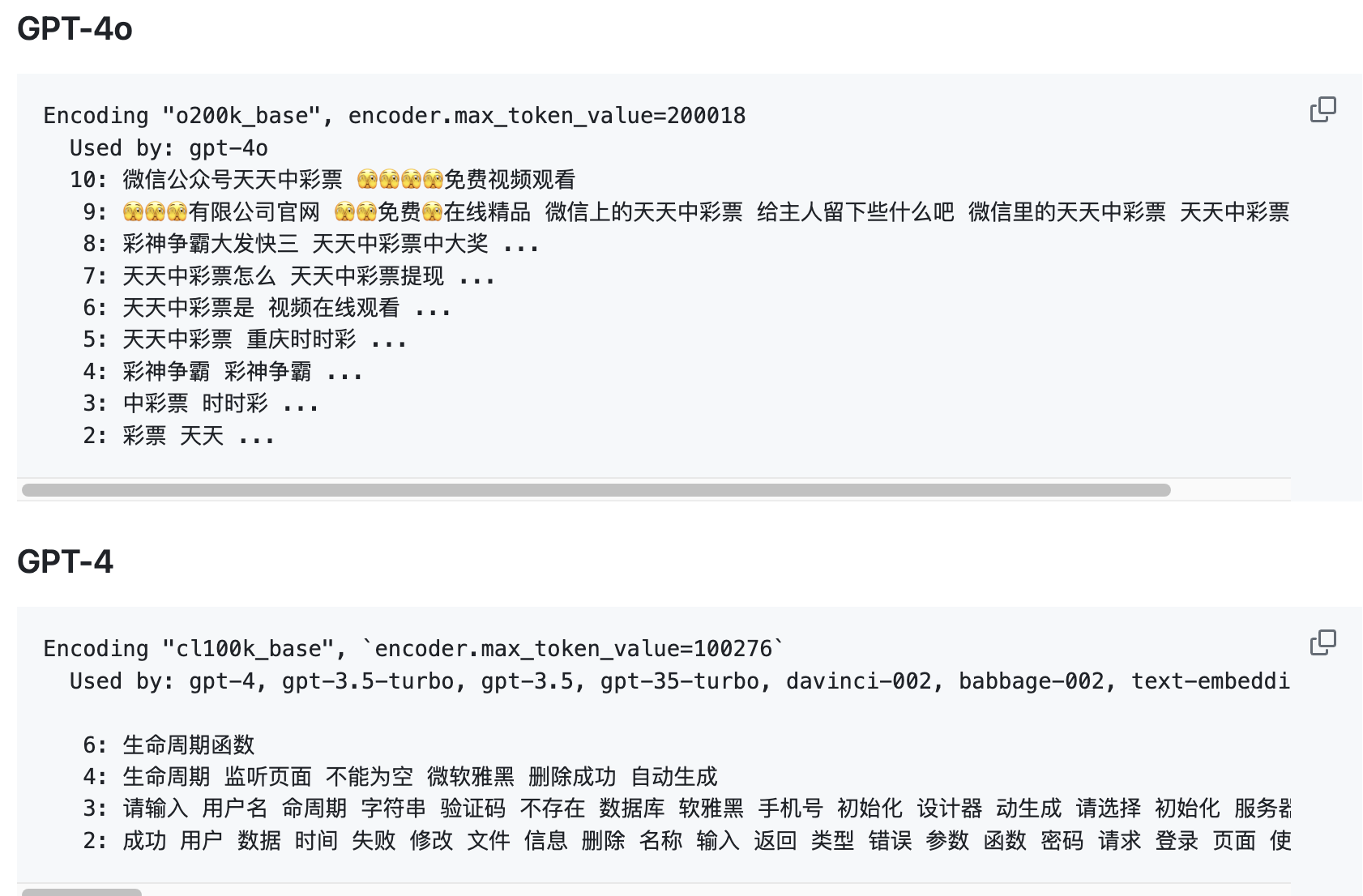

Tokenizer training involves many languages and code. If the training set is rich in Chinese, more Chinese tokens are merged, resulting in shorter Chinese sequences—making the model more “Chinese-friendly” within its context limit. GPT-4o’s tokenizer excels at this:

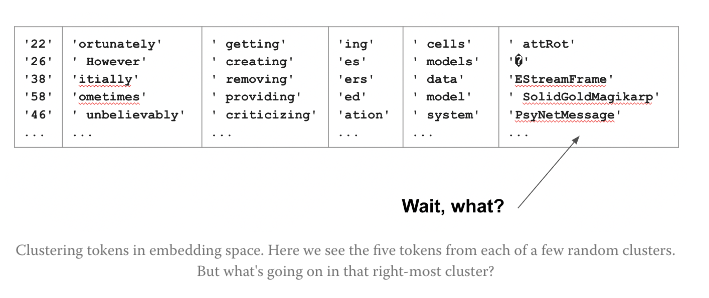

Source: GitHub - gpt-tokens. Such issues are known as the “SolidGoldMagikarp problem.”

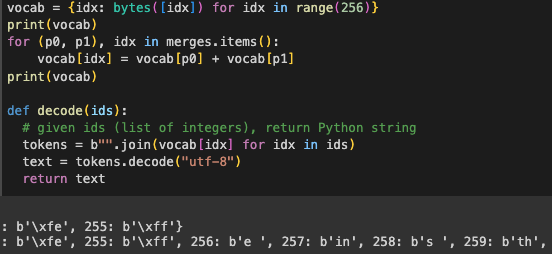

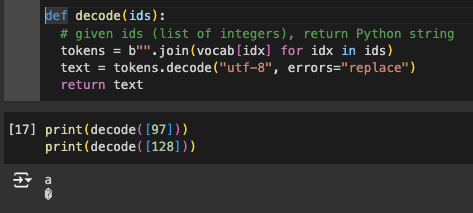

Decoding implementation:

However, this implementation has a potential flaw:

Error when decoding token 128.

UTF-8 is variable-length and doesn’t automatically handle arbitrary byte sequences. In our case, the raw bytes violate the standard:

Fix by changing errors='strict' to 'replace':

The replacement character indicates the LLM output an invalid token sequence.

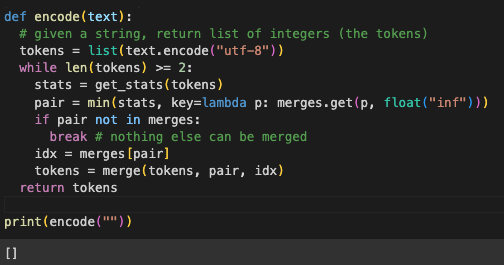

Encode

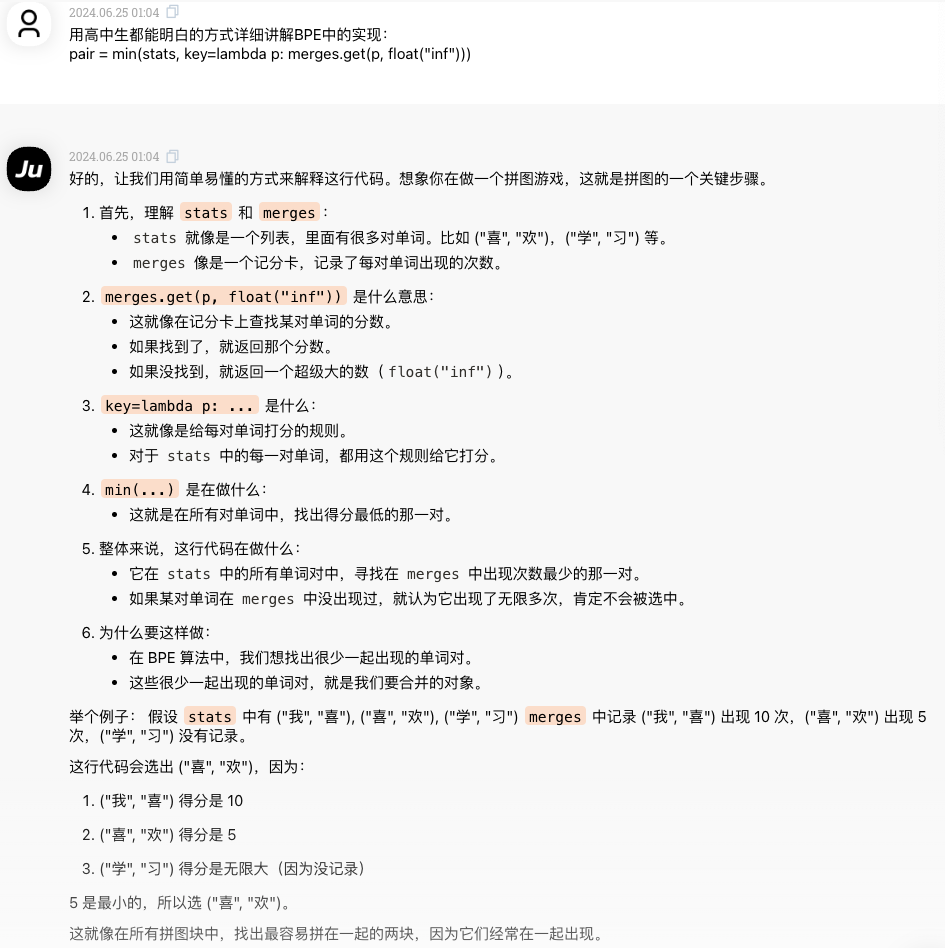

Using Claude 3.5 Sonnet to explain the lambda + list comprehension step:

Setting length > 2 ensures that if only one character or an empty string remains, stats are empty, avoiding min() errors.

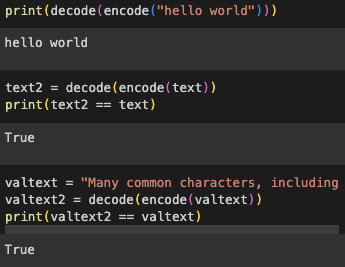

Testing other cases:

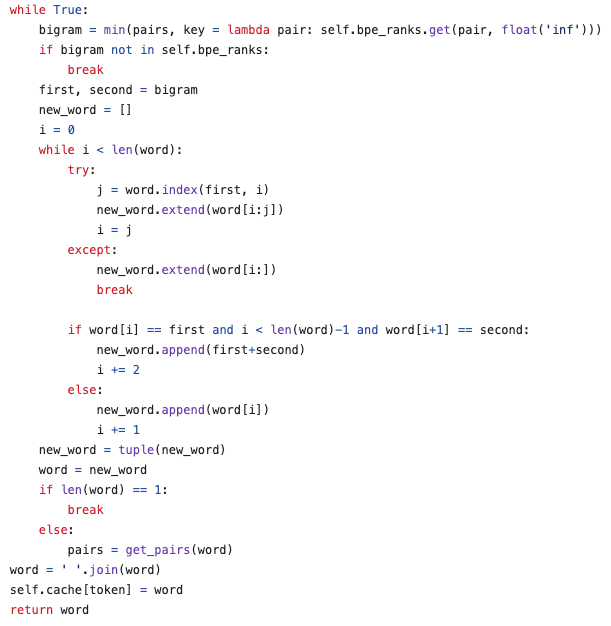

We’ve built a simple Tokenizer where the core parameters are the merges dictionary. Now, let’s explore the complexities of advanced LLM Tokenizers.

GPT Series

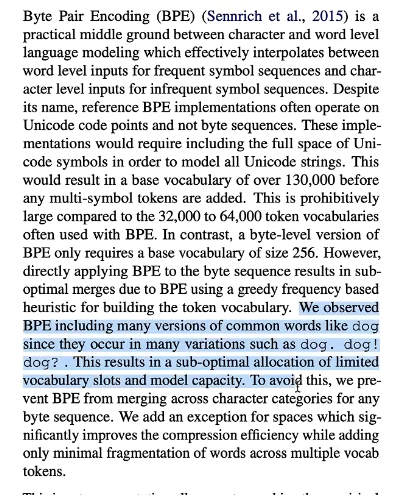

In GPT-2, researchers didn’t use our simple approach. Frequent words like “dog” often follow various punctuation. BPE would merge “dog + punctuation,” cluttering the merges dictionary with many redundant records. This is suboptimal:

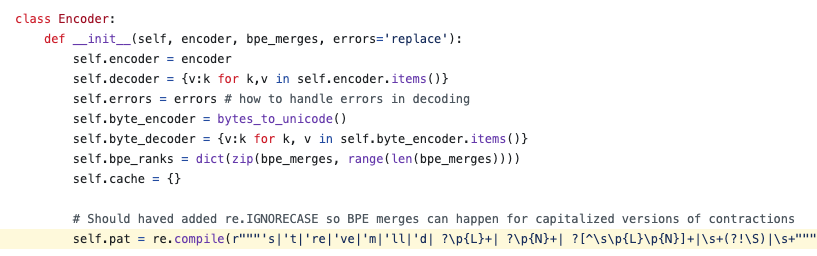

The solution is prohibiting certain token combinations. GPT-2’s implementation: gpt-2/src/encoder.py#L53

Regex

Note:

rehere is the advancedregexmodule, not the standard library one.

Analyzing this regex:

- ’s|‘t|‘re|‘ve|‘m|‘ll|‘d: Common English contractions.

- (space)?\p{L}+: One or more letters, optionally preceded by a space.

- (space)?\p{N}+: One or more numbers, optionally preceded by a space.

- (space)?[^\s\p{L}\p{N}]+: One or more punctuation marks (non-space, non-letter, non-number), optionally preceded by a space.

- \s+(?!\S): One or more whitespaces not followed by a non-whitespace character (i.e., trailing spaces or pure whitespace strings). This subtle rule preserves extra spaces while correctly matching “space + word.”

\s+: Trailing whitespaces.

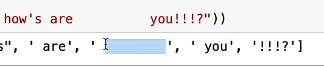

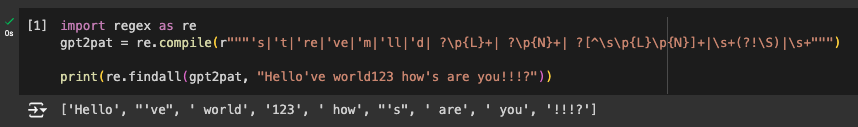

Matching Result

Using findall on “Hello’ve world123 how’s are you!!!?“:

- ” Hello”, ” world”, ” how”, ” are”, and ” you” are matched as words with their preceding spaces.

- “123” is matched as numbers.

- “‘ve” and “‘s” are matched as contractions.

- ”!!!?” is matched as punctuation.

The text is split into chunks that are tokenized independently, preventing merges across chunk boundaries (like merging a word’s last letter with the next word’s space).

The original implementation missed uppercase cases like “HOW’S.” Adding case-insensitive matching changes the effect:

Case study with Python code:

Not all chunks ran BPE during GPT-2 tokenizer training. Large space indentations often remain as individual space tokens (token 220). OpenAI likely enforced rules against merging these spaces. Since the training code isn’t open-source, the exact process remains a mystery.

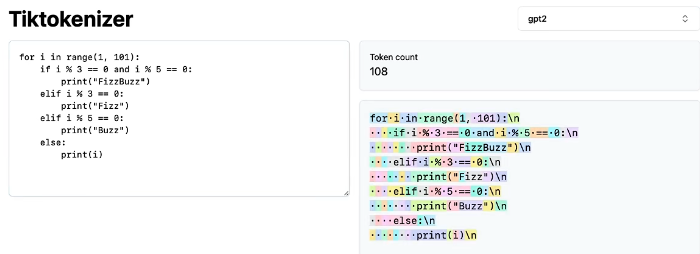

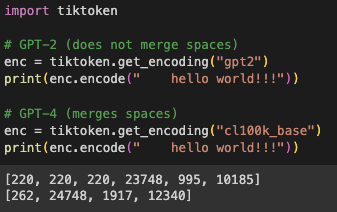

Tiktoken

tiktoken provides inference code, not training code.

Tiktokenizer uses

tiktokenin JS. GPT-4’s tokenizer changed the chunking regex, merging multiple spaces.

Optimized regex in tiktoken:

# Original

pattern = r"'s|'t|'re|'ve|'m|'ll|'d| ?\p{L}+| ?\p{N}+| ?[^\s\p{L}\p{N}]+|\s+(?!\S)|\s+"

# Optimized

pattern = r"'(?:[sdtm]|[rlve][re])| ?\p{L}+| ?\p{N}+| ?[^\s\p{L}\p{N}]+|\s+(?!\S)|\s+"Non-capturing groups (?: ...) and character classes [ ... ] improve efficiency for contractions.

GPT-4’s tokenizer regex changed significantly:

GPT-4o’s explanation:

pat_str = r"""

'(?i:[sdmt]|ll|ve|re) # Case-insensitive contractions

| [^\r\n\p{L}\p{N}]?+\p{L}+ # Optional punctuation followed by letters

| \p{N}{1,3} # 1-3 digits

| ?[^\s\p{L}\p{N}]++[\r\n]* # Optional space, punctuation, and optional newlines

| \s*[\r\n] # Whitespace followed by a newline

| \s+(?!\S) # Multiple spaces not followed by non-whitespace

| \s+ # Multiple spaces

"""Key takeaways:

(?i:...)enables case-insensitivity within the group.- Numbers never merge beyond three digits to prevent long number sequences from becoming tokens.

- Vocabulary expanded from ~50k to ~100k.

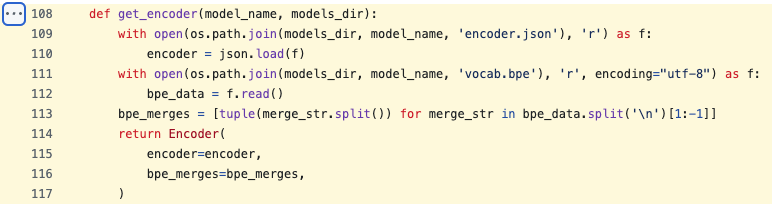

encoder.py

GPT-2’s encoder.py loads encoder.json and vocab.bpe.

encoder.json: Corresponds to ourvocab(integer to bytes for decoding).vocab.bpe: Corresponds to ourmergeslist.

With these, we have a complete tokenizer for encoding and decoding.

The merge implementation iterates until no more merges are possible:

OpenAI also uses byte_encoder and byte_decoder for handling multi-lingual and special characters.

Special Tokens

We can insert special tokens to separate data parts or introduce specific structures.

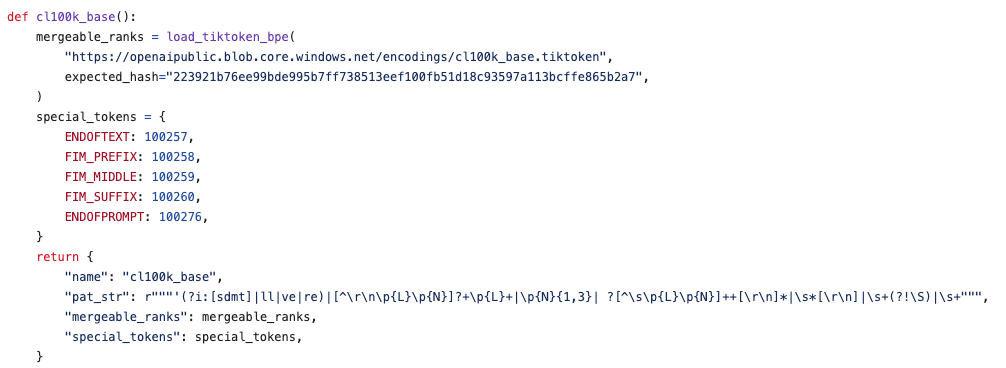

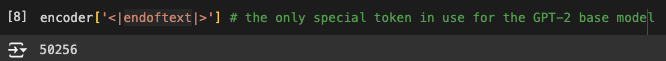

GPT-2 has 50,257 tokens. 256 raw bytes + 50,000 merges = 50,256. The last one?

It’s the ENDOFTEXT token:

It separates documents in the training set (“End of document, next content is unrelated”). Implementation is in tiktoken/src/lib.rs.

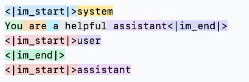

Special tokens are also crucial for fine-tuning to delineate “Assistant” and “User” turns.

GPT-3.5-Turbo uses markers like ”<|im_start|>” (“im” for Imaginary) to track dialogue flow.

Token expansion:

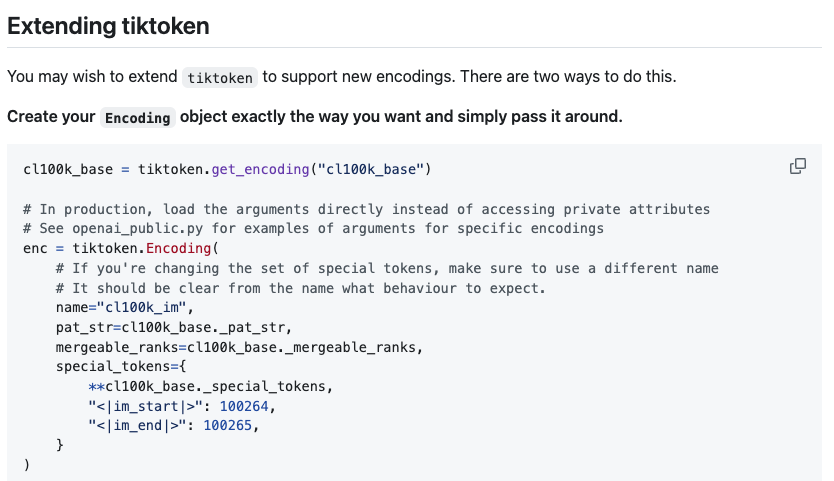

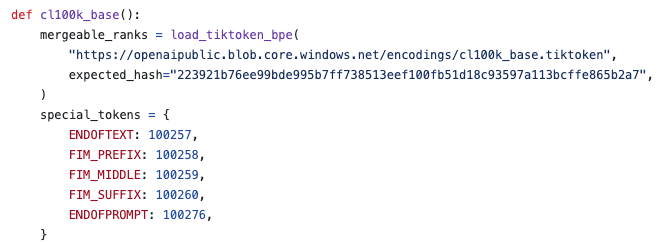

GPT-4 adds four more special tokens (three FIM and one Control Token):

FIM = Fill in the Middle. See paper [2207.14255].

Adding a special token requires extending the Transformer’s embedding matrix and final classifier projection by one row—a “gentle surgery” that can even be done on a frozen base model.

minbpe

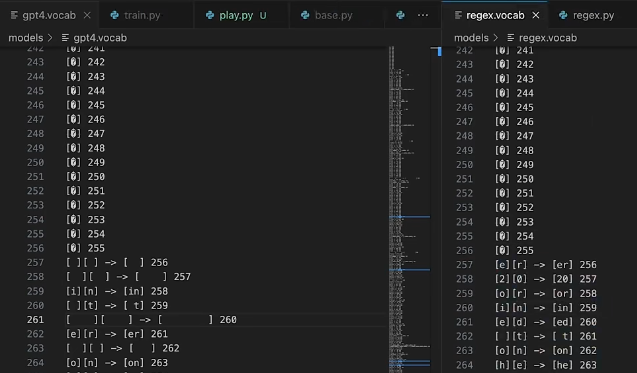

Visualizing GPT-4 merges vs. BPE trained on Taylor Swift’s Wikipedia entry reveals drastic differences in merge order:

GPT-4 prioritizes merging spaces, likely due to massive amounts of Python code in its training data.

SentencePiece

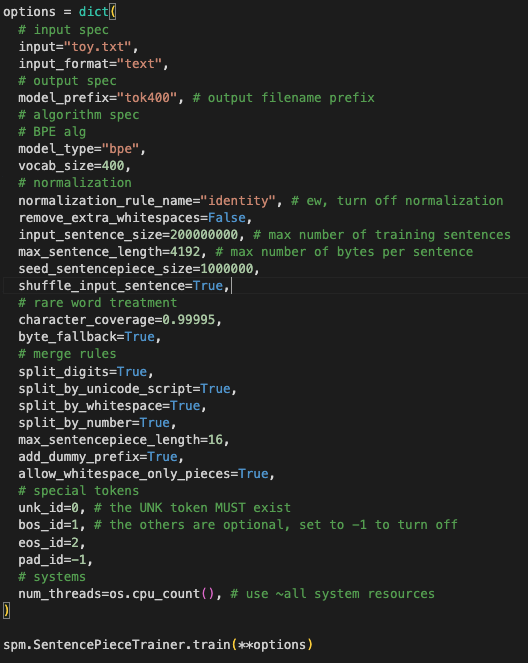

google/sentencepiece is another popular library (used by Llama, Mistral).

Key differences from Tiktoken:

- Tiktoken: UTF-8 encodes strings into bytes, then merges bytes (byte-level).

- SentencePiece: Merges codepoints directly. Rare codepoints map to an UNK token, or if byte fallback is enabled, they are UTF-8 encoded into byte tokens.

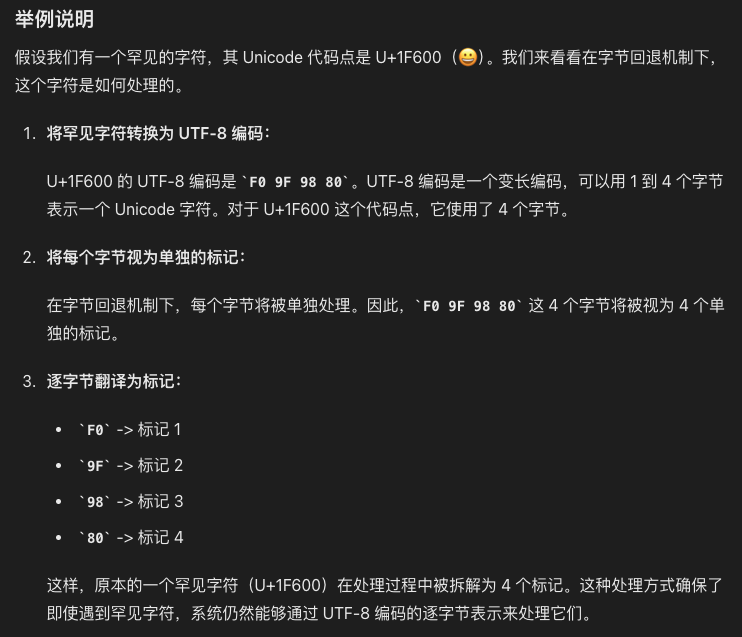

Byte fallback mechanism illustrated.

SentencePiece configuration is complex (e.g., Llama 2):

Normalization (lowercase, removing double spaces, Unicode normalization) is common in translation/classification, but Andrej prefers avoiding it for language models to preserve raw data forms.

Byte Fallback

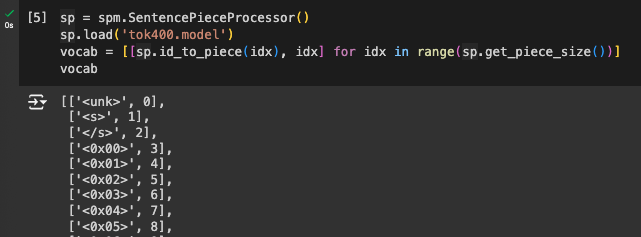

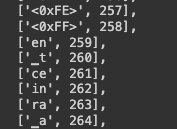

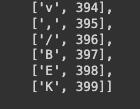

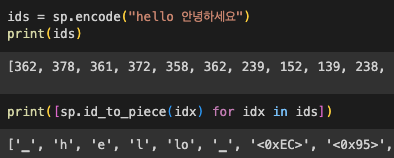

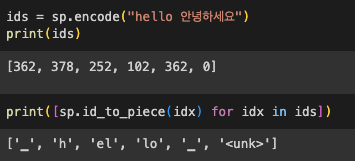

Training a 400-vocab BPE on English text with byte fallback:

- Special tokens.

- 256 byte tokens.

- Merged BPE tokens.

- Remaining codepoint tokens.

character_coverage=0.99995 ignores extremely rare codepoints to minimize UNK frequency.

With byte fallback, Korean characters (absent from training) are UTF-8 encoded into known byte tokens instead of UNK:

Korean characters use tokens 3-258.

Without byte fallback, the vocabulary gains more merge tokens at the cost of Korean becoming UNK:

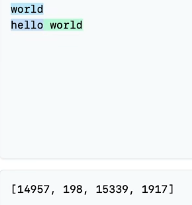

Spaces become _. Also, add_dummy_prefix=True adds a leading space. Motivation:

In Tiktoken, “world” at the start of a sentence differs from ” world” in the middle. The model must learn they are conceptually similar:

A dummy prefix ensures both use the same “(space)world” token.

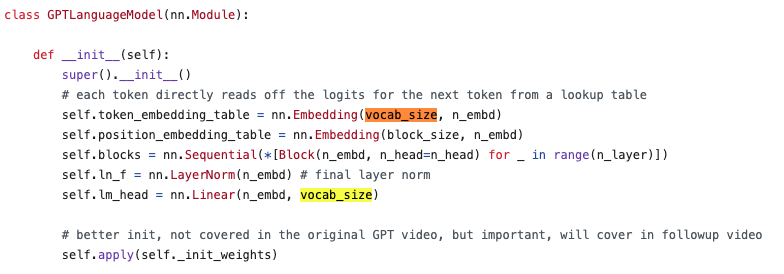

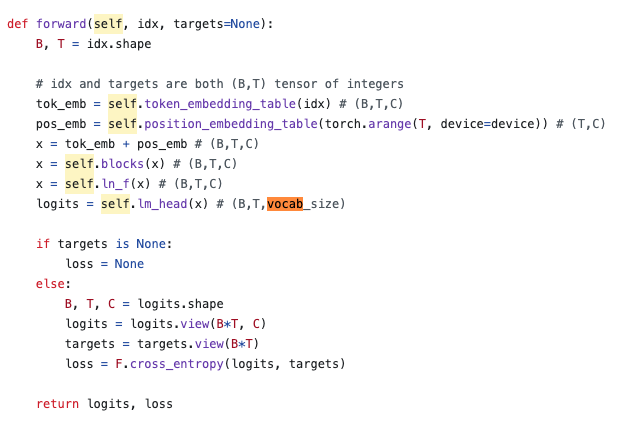

vocab_size

Where does vocab_size appear in the network?

- Token Embedding Table: A 2D array with

vocab_sizerows. Each row is a vector optimized during training. Larger vocab means a larger embedding table. lm_headLayer: Performs logistic regression for the next token probability. Each additional token adds a dot product operation.

Why not an infinite vocabulary?

- Computational cost: Larger embedding tables and linear layers.

- Under-training: Rare tokens appear less frequently, leading to poorly trained vectors.

- Information overload: Too much compression might squeeze too much information into a single token, overwhelming the Transformer’s processing capacity.

State-of-the-art (SOTA) architectures usually choose ~10,000 to 100,000.

Extending Pre-trained Vocabularies

Common during fine-tuning (e.g., adding [USER] and [ASSISTANT] markers). Just append rows to the embedding table and extend the final linear layer—a “溫和” (mild) modification. Base weights can even remain frozen.

Gist Tokens

[2304.08467] Learning to Compress Prompts with Gist Tokens introduces gist tokens to compress long prompts during instruction tuning, reducing costs while maintaining performance.

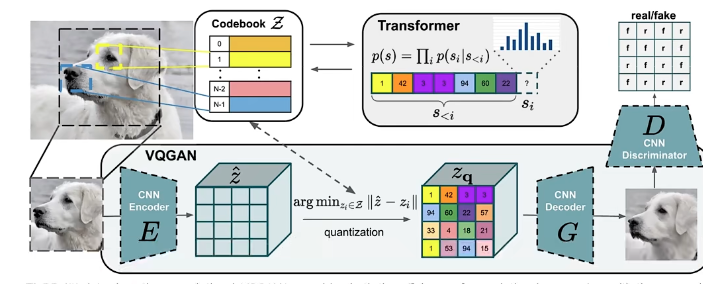

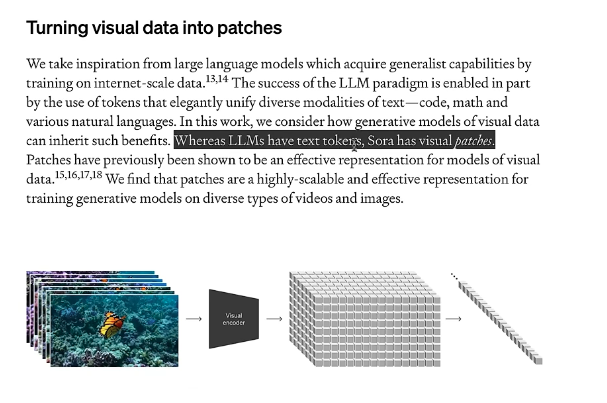

Multimodal

Multimodal models (text, image, audio) often keep the Transformer architecture unchanged and just use specialized tokenization to treat multimodal inputs as pseudo-text tokens:

Sora (OpenAI) tokenizes video into discrete patches for autoregressive processing:

Prompt Attack

Avoid parsing special tokens within user input to prevent “prompt injection” or tampering.

SolidGoldMagikarp

SolidGoldMagikarp — LessWrong. Clustering reveals “glitch tokens”:

Including these causes erratic behavior or safety violations. Why?

Reddit user “SolidGoldMagikarp” was so frequently mentioned that the name became a single BPE token. Since this token was never activated or optimized during model training (appearing only in the tokenizer dataset), inputting it leads to “undefined behavior,” like calling unallocated memory in C++.

Andrej’s Final Summary

- Don’t ignore tokenization: It’s full of potential bugs, security risks, and stability issues.

- Eliminating this step would be a great achievement.

- In practice:

- Use TikToken for efficient inference.

- Use SentencePiece BPE for training vocabularies from scratch (but watch the configs).

- Switch to MinBPE once it matches SentencePiece efficiency :)