Learn the progressive fusion concept of WaveNet and implement a hierarchical tree structure to build deeper language models.

History of LLM Evolution (4): WaveNet — Convolutional Innovation in Sequence Models

The source code repository for this section.

In previous sections, we built a character-level language model using a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). Now, it’s time to make its structure more complex. Our current goal is to allow more characters in the input sequence (currently 3). Furthermore, we don’t want to squeeze all of them into a single hidden layer to avoid over-compressing information. This leads us to a deeper model similar to WaveNet.

WaveNet

Published in 2016, WaveNet is essentially a language model, but it predicts audio sequences instead of character or word-level sequences. Fundamentally, the modeling setup is the same—both are Autoregressive Models trying to predict the next element in a sequence.

The paper uses a hierarchical tree structure for prediction, which we will implement in this section.

nn.Module

We’ll encapsulate the previous content into classes, mimicking the PyTorch nn.Module API. This allows us to think of modules like “Linear,” “1D Batch Norm,” and “Tanh” as Lego bricks used to build neural networks:

class Linear:

def __init__(self, fan_in, fan_out, bias=True):

self.weight = torch.randn((fan_in, fan_out), generator=g) / fan_in**0.5

self.bias = torch.zeros(fan_out) if bias else None

def __call__(self, x):

self.out = x @ self.weight

if self.bias is not None:

self.out += self.bias

return self.out

def parameters(self):

return [self.weight] + ([] if self.bias is None else [self.bias])Linear layer module: Its role is to perform a matrix multiplication during the forward pass.

class BatchNorm1d:

def __init__(self, dim, eps=1e-5, momentum=0.1):

self.eps = eps

self.momentum = momentum

self.training = True

# Parameters trained via backpropagation

self.gamma = torch.ones(dim)

self.beta = torch.zeros(dim)

# Buffers trained via "momentum updates"

self.running_mean = torch.zeros(dim)

self.running_var = torch.ones(dim)

def __call__(self, x):

# Calculate forward pass

if self.training:

xmean = x.mean(0, keepdim=True) # Batch mean

xvar = x.var(0, keepdim=True) # Batch variance

else:

xmean = self.running_mean

xvar = self.running_var

xhat = (x - xmean) / torch.sqrt(xvar + self.eps) # Normalize data to unit variance

self.out = self.gamma * xhat + self.beta

# Update buffers

if self.training:

with torch.no_grad():

self.running_mean = (1 - self.momentum) * self.running_mean + self.momentum * xmean

self.running_var = (1 - self.momentum) * self.running_var + self.momentum * xvar

return self.out

def parameters(self):

return [self.gamma, self.beta]Batch-Norm:

- Has

running_mean&running_varupdated outside of backpropagation. self.training = True: Since batch norm behaves differently in training vs. evaluation, we need a training flag to track its state.- Performs coupled calculations on elements within a batch to control activation statistics and reduce Internal Covariate Shift.

class Tanh:

def __call__(self, x):

self.out = torch.tanh(x)

return self.out

def parameters(self):

return []Instead of a local torch.Generator g, we’ll set a global random seed:

torch.manual_seed(42);The following should look familiar, including the embedding table C and our layer structure:

n_embd = 10 # Dimension of character embedding vectors

n_hidden = 200 # Number of neurons in the MLP hidden layer

C = torch.randn((vocab_size, n_embd))

layers = [

Linear(n_embd * block_size, n_hidden, bias=False),

BatchNorm1d(n_hidden),

Tanh(),

Linear(n_hidden, vocab_size),

]

# Initialize parameters

with torch.no_grad():

layers[-1].weight *= 0.1 # Scale down the last layer (output layer) to reduce initial confidence

parameters = [C] + [p for layer in layers for p in layer.parameters()]

'''

List comprehension, equivalent to:

for layer in layers:

for p in layer.parameters():

p...

'''

print(sum(p.nelement() for p in parameters)) # total number of parameters

for p in parameters:

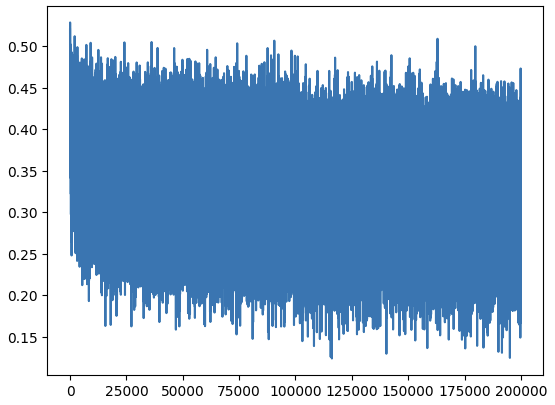

p.requires_grad = TrueThe optimization training part remains unchanged for now. We notice the loss function curve has high fluctuations because a batch size of 32 is too small—each batch can be very “lucky” or “unlucky” (high noise).

During evaluation, we must set the training flag to False for all layers (currently only affecting batch norm):

# Set layers to evaluation mode

for layer in layers:

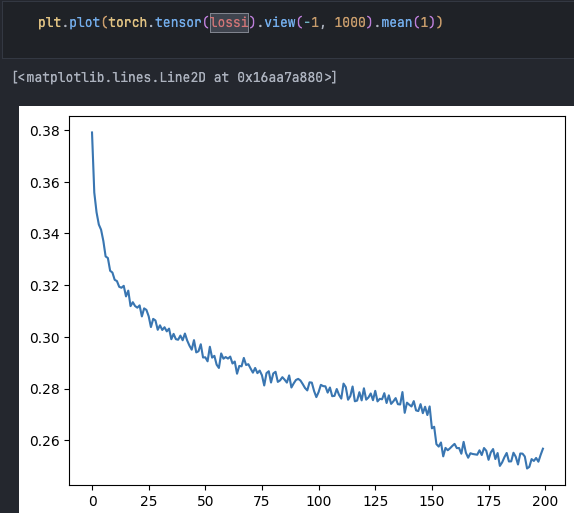

layer.training = FalseLet’s fix the loss function visualization:

lossi is a list of all losses. We’ll average the values inside to get a more representative curve.

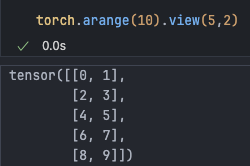

Reviewing torch.view():

Equivalent to

view(5, -1)

This is convenient for unfolding values in a list.

torch.tensor(lossi).view(-1, 1000).mean(1)

Looks much better now. We can observe the learning rate reduction reaching local minima.

Next, we turn the previous Embedding and Flattening operations into modules:

emb = C[Xb]

x = emb.view(emb.shape[0], -1)class Embedding:

def __init__(self, num_embeddings, embedding_dim):

self.weight = torch.randn((num_embeddings, embedding_dim))

# C now becomes embedding weights

def __call__(self, IX):

self.out = self.weight[IX]

return self.out

def parameters(self):

return [self.weight]

class FlattenConsecutive:

def __call__(self, x):

self.out = x.view(x.shape[0], -1)

return self.out

def parameters(self):

return []PyTorch has a container concept, essentially a way to organize layers as lists or dictionaries. Sequential is one such container that passes input through all layers in order:

class Sequential:

def __init__(self, layers):

self.layers = layers

def __call__(self, x):

for layer in self.layers:

x = layer(x)

self.out = x

return self.out

def parameters(self):

# Get parameters from all layers and flatten into a list

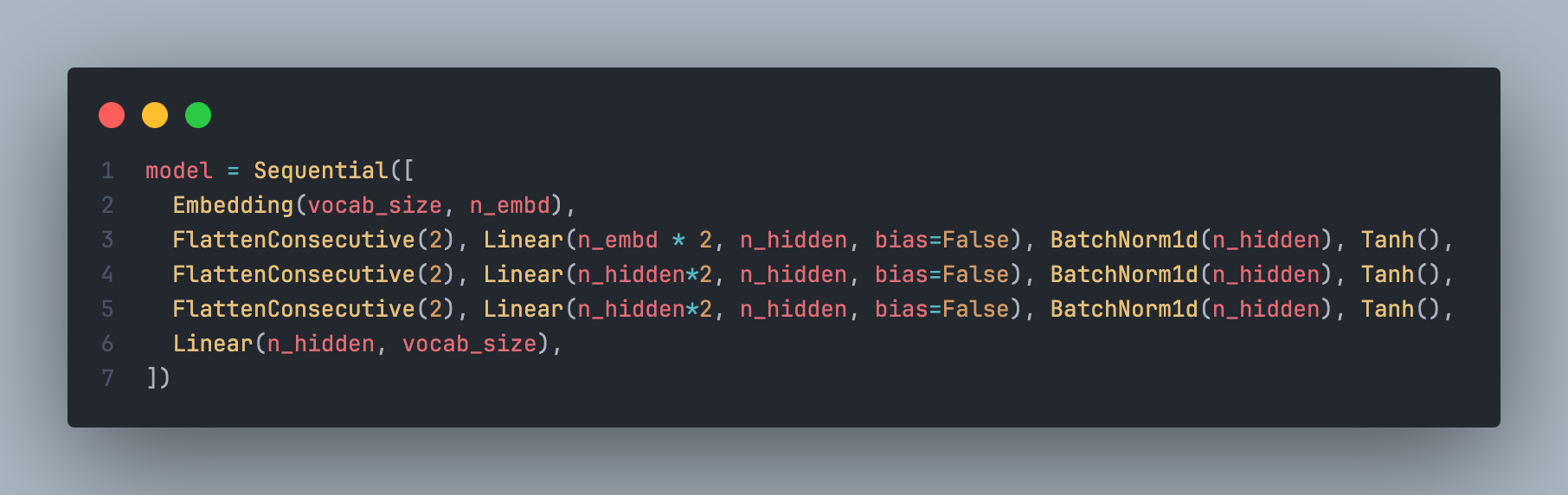

return [p for layer in self.layers for p in layer.parameters()]Now we have a Model concept:

model = Sequential([

Embedding(vocab_size, n_embd),

Flatten(),

Linear(n_embd * block_size, n_hidden, bias=False),

BatchNorm1d(n_hidden), Tanh(),

Linear(n_hidden, vocab_size),

])

parameters = model.parameters()

print(sum(p.nelement() for p in parameters)) # total parameter count

for p in parameters:

p.requires_grad = TrueThis yields further simplification:

# forward pass

logits = model(Xb)

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, Yb) # loss function

# evaluate the loss

logits = model(x)

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, y)

# sample from the model

# forward pass the neural net

logits = model(torch.tensor([context]))

probs = F.softmax(logits, dim=1)Implementing the Hierarchical Structure

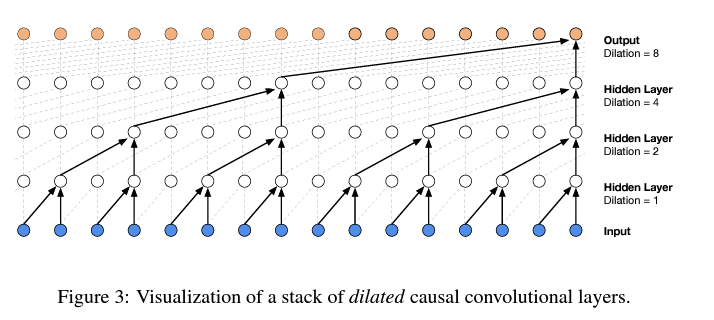

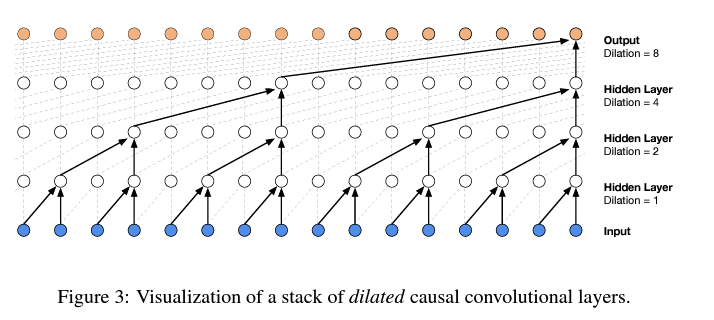

We don’t want to squeeze all information into one layer in one step like our current model. Instead, like WaveNet, we want to predict the next character by fusing two characters into a two-character representation, then into four-character blocks, and so on, progressively fusing information into the network through a hierarchical tree structure.

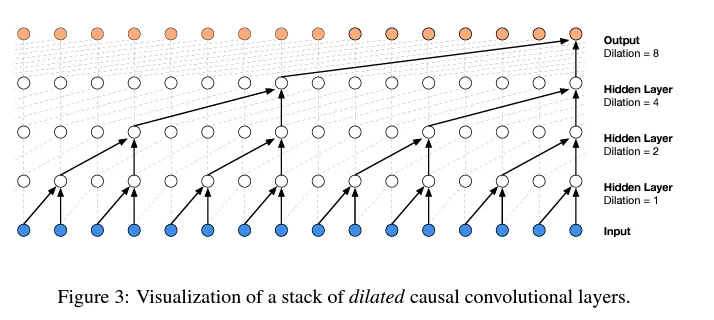

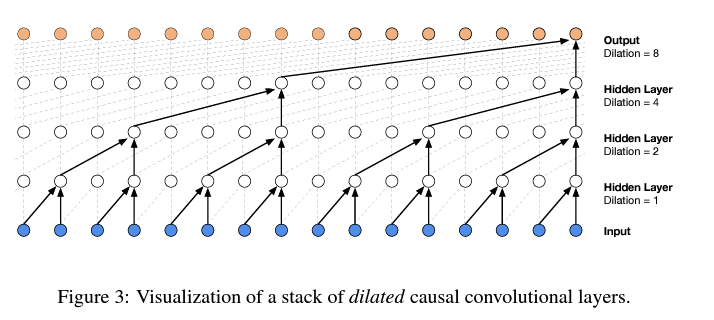

In WaveNet, this diagram visualizes a “Dilated causal convolution layer.” Don’t worry about the specifics; we are focusing on the core idea: Progressive fusion.

Increase context input and process these 8 characters in a tree structure:

# block_size = 3

# train 2.0677597522735596; val 2.1055991649627686

block_size = 8Simply expanding the context length improves performance:

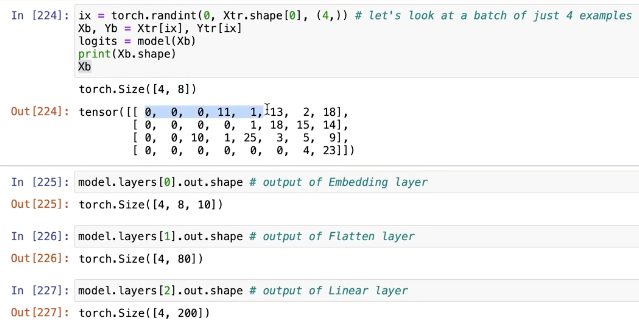

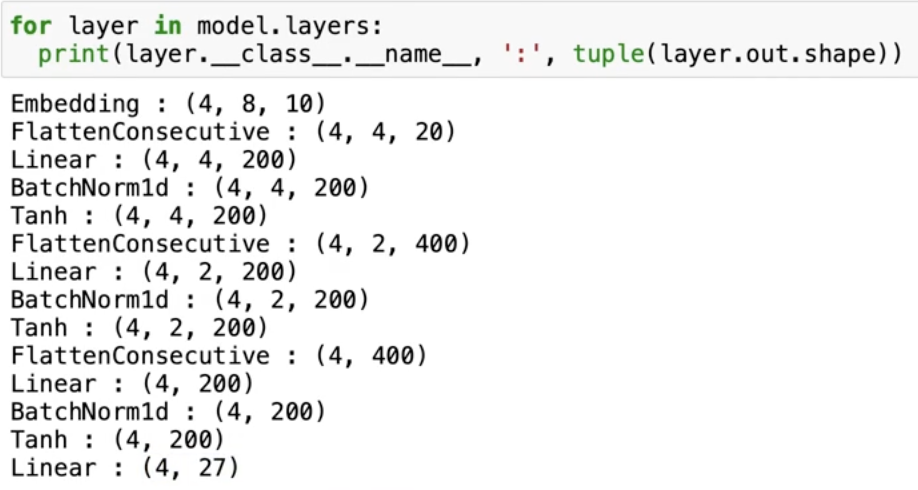

To understand what we’re doing, let’s observe the tensor shapes as they pass through layers:

Inputting 4 random numbers with block_size=8 gives a shape of 4x8.

- After the first layer (embedding), we get a 4x8x10 output—meaning our embedding table has a learned 10D vector for each character.

- After the second layer (flatten), it becomes 4x80. This layer stretches the 10D embeddings of these 8 characters into one long row, like a concatenation operation.

- The third layer (linear) uses matrix multiplication to turn these 80 numbers into 200 channels.

To recap what the Embedding layer does:

This answer explains it perfectly:

- Turns a sparse matrix into a dense matrix through linear transformation (table lookup).

- This dense matrix uses N features to represent all words. Coefficients represent relationships between words and features, encapsulating deep relationships between words.

- The weights are encoding parameters learned by the embedding layer, which are continuously optimized during backpropagation.

A linear layer takes input X, multiplies it by weights, and optionally adds a bias:

def __init__(self, fan_in, fan_out, bias=True):

self.weight = torch.randn((fan_in, fan_out)) / fan_in**0.5 # note: kaiming init

self.bias = torch.zeros(fan_out) if bias else NoneWeights are 2D, bias is 1D.

Based on input/output shapes, the linear layer looks like this internally:

(torch.randn(4, 80) @ torch.randn(80, 200) + torch.randn(200)).shapeOutput is 4x200. Bias addition follows broadcasting semantics.

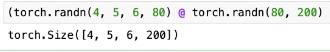

Note that PyTorch matrix multiplication supports high-dimensional tensors, operating only on the last dimension while treating others as batch dimensions.

This is very useful for our next goal: parallel batch dimensions. Instead of inputting 80 numbers at once, we want two characters fused together in the first layer—inputting 20 numbers, like so:

# (1 2) (3 4) (5 6) (7 8)

(torch.randn(4, 4, 20) @ torch.randn(20, 200) + torch.randn(200)).shapeThis becomes four sets of bigrams, each a 10D vector.

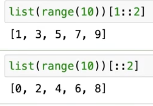

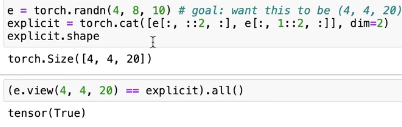

To implement this, Python provides a convenient way to slice even and odd parts of a list:

e = torch.randn(4, 8, 10)

torch.cat([e[:, ::2, :], e[:, 1::2, :]], dim=2)

# torch.Size([4, 4, 20])This explicitly extracts even and odd parts and concatenates the two 4x4x10 parts together.

The powerful

view()can do equivalent work.

Now, let’s refine our Flatten layer. Create a constructor that takes the number of consecutive elements we want to concatenate in the last dimension.

class FlattenConsecutive:

def __init__(self, n):

self.n = n

def __call__(self, x):

B, T, C = x.shape

x = x.view(B, T//self.n, C*self.n)

if x.shape[1] == 1:

x = x.squeeze(1)

self.out = x

return self.out

def parameters(self):

return []- B: Batch size, number of samples.

- T: Time steps, length of the sequence.

- C: Channels or Features per time step.

Input Tensor: Input

xis a 3D tensor of shape(B, T, C).Flattening Operation: By calling

x.view(B, T//self.n, C*self.n), the class merges consecutive time steps.self.nis the number of steps to merge. This results in each new time step being a wider feature vector containing information fromnoriginal steps. Time dimensionTis reduced byn, while feature dimensionCis increased byn.Removing Unit Dimension: If the resulting time dimension is 1 (

x.shape[1] == 1),x.squeeze(1)removes it, bringing us back to the 2D case we saw before.

Check the shapes of intermediate layers after the change:

In batch norm, we want to maintain mean and variance for only 68 channels, not 32x4 dimensions. So we update the BatchNorm1d implementation:

class BatchNorm1d:

def __call__(self, x):

# calculate the forward pass

if self.training:

if x.ndim == 2:

dim = 0

elif x.ndim == 3:

dim = (0,1) # torch.mean() can take a tuple of dimensions

xmean = x.mean(dim, keepdim=True) # batch mean

xvar = x.var(dim, keepdim=True) # batch varianceNow

running_mean.shapeis [1, 1, 68].

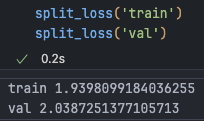

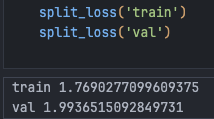

Scaling Up the Network

With the improvements complete, we now further increase performance by increasing network size.

n_embd = 24 # Embedding dimension

n_hidden = 128 # Number of neurons in MLP hidden layerParameter count reaches 76,579, and performance breaks the 2.0 barrier:

By now, training time has significantly increased. Despite performance gains, setting hyperparameters like learning rate still feels like blind debugging, constantly monitoring training loss.

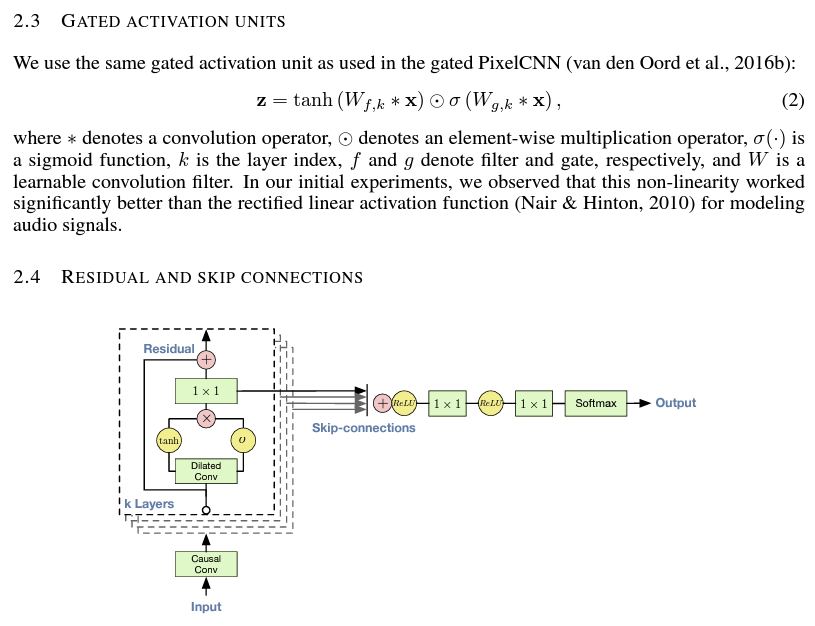

Convolution

In this section, we implemented the main architecture of WaveNet but didn’t implement the specific forward pass involving more complex gated linear layers, Residual connections, and Skip connections.

Let’s briefly understand how our tree structure relates to the Convolutional Neural Networks used in the WaveNet paper.

Essentially, we use Convolution for efficiency. It allows us to slide the model over the input sequence, performing the loops (sliding the kernel and calculating) within CUDA kernels.

We implemented a single black structure from the diagram to get one output, but convolution lets you apply this black structure across the input sequence, calculating all orange outputs simultaneously like a linear filter.

Efficiency gains:

- Loops are done in CUDA cores.

- Variable reuse: For example, a white dot in the second layer is both the left child of one third-layer dot and the right child of another. The node value is used twice.

Summary

After this section, the torch.nn module is unlocked, and we will transition to using it for future model implementations.

Reflecting on this section, a lot of time was spent getting layer shapes right. Andrej always debugs shapes in a Jupyter Notebook before copying the satisfied code into VS Code.