Learning from Andrej Karpathy's micrograd project, we build an automatic differentiation framework from scratch to deeply understand the core principles of backpropagation and the chain rule.

Building a Minimal Autograd Framework from Scratch

Code Repository: https://github.com/karpathy/nn-zero-to-hero

Andrej Karpathy is the author and lead instructor of the famous deep learning course Stanford CS 231n, and a co-founder of OpenAI. “micrograd” is a tiny, educational project he created. It implements a simplified autograd and gradient descent library, requiring only basic calculus knowledge, intended for teaching and demonstration.

Introduction to Micrograd

Micrograd is essentially an autograd engine. Its true purpose is implementing backpropagation.

Backpropagation is an algorithm that efficiently calculates the gradient of a loss function with respect to weights in a neural network. This allows for iterative weight adjustment to minimize the loss, improving accuracy. Thus, backpropagation is the mathematical core of modern libraries like PyTorch or JAX.

Operations supported by micrograd:

from micrograd.engine import Value

a = Value(-4.0)

b = Value(2.0)

c = a + b # C maintains pointers to A and B

d = a * b + b**3

c += c + 1

c += 1 + c + (-a)

d += d * 2 + (b + a).relu()

d += 3 * d + (b - a).relu()

e = c - d

f = e**2

g = f / 2.0

g += 10.0 / f # Forward pass output

print(f'{g.data:.4f}') # prints 24.7041

g.backward() # Initialize backpropagation at G, recursively applying the chain rule

print(f'{a.grad:.4f}') # prints 138.8338, numerical dg/da

print(f'{b.grad:.4f}') # prints 645.5773, numerical dg/dbThis tells us how G responds to tiny positive adjustments in A and B.

The key lies in the Value class implementation, which we’ll explore below.

Neural Network Principles

Fundamentally, neural networks are mathematical expressions. They take input data and weights as inputs, outputting predictions or loss functions.

This engine works at the scalar level, breaking down into atomic operations like addition and multiplication. While you’d never do this in production, it’s perfect for learning as it avoids the complexity of n-dimensional tensors used in modern libraries. The math remains identical.

Understanding Derivatives

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import math

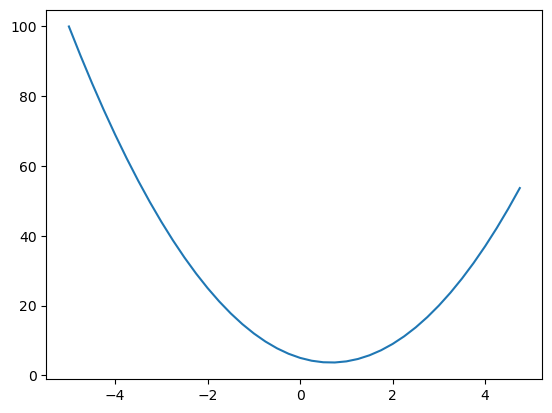

%matplotlib inline# Define a scalar function f(x)

def f(x):

return 3*x**2 - 4*x + 5

f(3.0)20.0

# Create scalar values for f(x)

xs = np.arange(-5, 5, 0.25)

# Apply f(x) to each xs

ys = f(xs)

# Plot

plt.plot(xs, ys)

What is the derivative at each x?

Analytically, f’(x) = 6x - 4. But in neural networks, nobody writes out the full expression symbolically because it would be gargantuan.

Definition of a Derivative

Let’s look at the definition of a derivative to ensure deep understanding.

# Numerical derivative using a tiny h

h = 0.00000001

x = 3.0

(f(x + h) - f(x)) / h # positive response14.00000009255109

This is the function’s response in the positive direction (rise over run).

At certain points, the response might be zero if the function doesn’t change when nudged, hence slope=0.

What Derivatives Tell Us

A more complex example:

a = 2.0

b = -3.0

c = 10

d = a * b + c

print(d)The output d is a function of three scalar inputs. We’ll examine the derivatives of d with respect to a, b, and c.

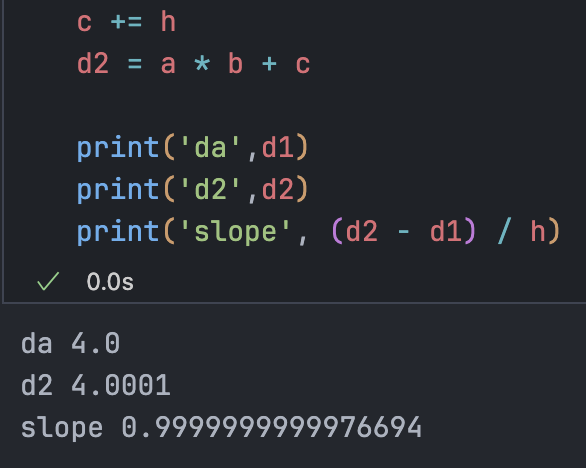

h = 0.0001

# inputs

a = 2.0

b = -3.0

c = 10

d1 = a * b + c

a += h

d2 = a * b + c

print('da', d1)

print('d2', d2)

print('slope', (d2 - d1) / h)Observe how d2 changes after nudging a.

Since a is positive and b is negative, increasing a reduces what is added to d, so d2 decreases.

da 4.0 d2 3.999699999999999 slope -3.000000000010772

Mathematically:

b += hda 4.0 d2 4.0002 slope 2.0000000000042206

The function increases by the same amount we add to c, so the slope is 1.

Now that we have intuition for how derivatives describe function responses, let’s move to neural networks.

Framework Implementation

Custom Data Structure

Neural networks are massive mathematical expressions, so we need a structure to maintain them.

class Value:

def __init__(self, data):

self.data = data

def __repr__(self):

return f"Value({self.data})"

def __add__(self, other):

out = Value(self.data + other.data)

return out

def __mul__(self, other):

out = Value(self.data * other.data)

return out

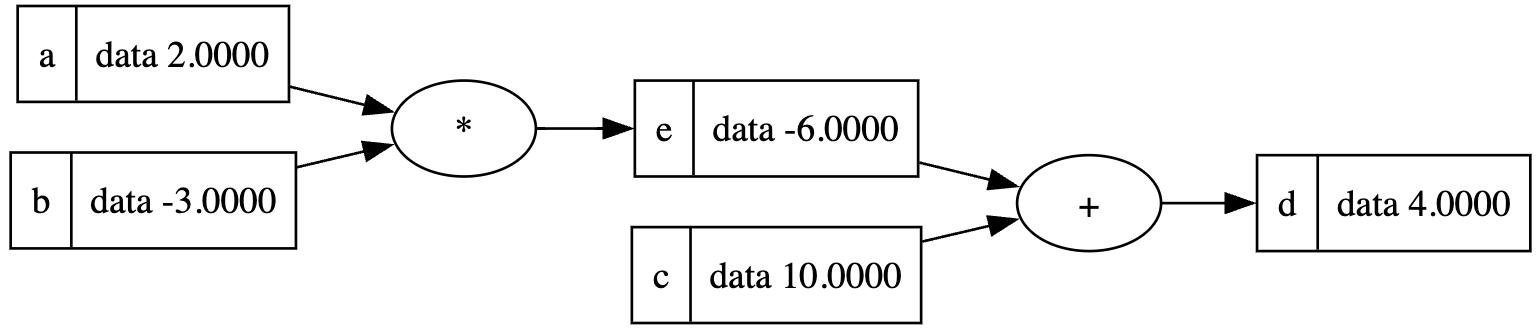

a = Value(2.0)

b = Value(-3.0)

c = Value(10.0)

d = a * b + c # (a.__mul__(b)).__add__(c)repr provides a clean print output.

We now need to track the expression structure—keeping pointers to the values that produced other values.

def __init__(self, data, _children=(), _op=''):

self.data = data

self._prev = set(_children)

self._op = _op

def __repr__(self):

return f"Value({self.data})"

def __add__(self, other):

out = Value(self.data + other.data, (self, other), '+')

return out

def __mul__(self, other):

out = Value(self.data * other.data, (self, other), '*')

return outNow we can trace children and the operations that created each value.

We need a way to visualize these growing expressions.

from graphviz import Digraph

def trace(root):

# builds a set of all nodes and edges in the graph

nodes, edges = set(), set()

def build(v):

if v not in nodes:

nodes.add(v)

for child in v._prev:

edges.add((child, v))

build(child)

build(root)

return nodes, edges

def draw_dot(root):

dot = Digraph(format='svg', graph_attr={'rankdir': 'LR'}) # LR = left to right

nodes, edges = trace(root)

for n in nodes:

uid = str(id(n))

dot.node(name = uid, label = "{ %s | data %.4f}" % (n.label, n.data), shape = 'record')

if n._op:

dot.node(name = uid + n._op, label = n._op)

dot.edge(uid + n._op, uid)

for n1, n2 in edges:

dot.edge(str(id(n1)), str(id(n2)) + n2._op)

return dot

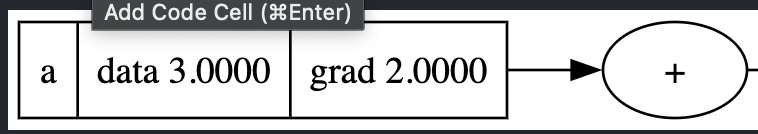

draw_dot(d)Add a label to the Value class:

a = Value(2.0, label='a')

b = Value(-3.0, label='b')

c = Value(10.0, label='c')

e = a * b; e.label = 'e'

d = e + c; d.label = 'd'

Going deeper:

f = Value(-2.0, label='f')

L = d * f; L.label = 'L'

draw_dot(L)Running Backpropagation

Starting from L, we’ll back-calculate gradients for all intermediate values. In neural networks, we’re interested in the derivative of weights with respect to the loss function L.

Add a grad variable to Value:

self.grad = 0Initially, we assume variables don’t affect the output (grad = 0).

What is dL/dL? If L changes by h, L changes by h, so the derivative is 1:

def lol():

h = 0.0001

# ... setup graph ...

L1 = L.data

# ... setup graph with L.data + h ...

L2 = L.data + h

print((L2 - L1) / h)

lol() # ~1.0L.grad = 1.0

# L = d * f

# dL/dd = f

f.grad = 4.0 # d.data

d.grad = -2.0 # f.datalol() performs an inline gradient check. Numerical gradients use small steps to estimate what backpropagation calculates exactly.

Now, how does L respond to C?

'''

d = c + e

dd / dc = 1.0

dd / de = 1.0

'''The + node only knows its local effect on its output d. We need dL/dc.

The answer is the Chain Rule: If z depends on y, and y depends on x, then: The chain rule tells you how to link derivatives together. As George F. Simmons said: “If a car travels twice as fast as a bicycle, and the bicycle is four times as fast as a walker, the car is 8 times as fast as the walker.” Multiply.

Addition Node: Gradient Distributor

In addition , local derivatives are 1. By the chain rule: Addition nodes distribute the upstream gradient “as-is” to all inputs.

Multiplication Node

For : .

Backpropagation core: recursively multiply on the local derivatives.

Nudging Inputs

Adjusting leaf nodes (which we control) to increase L. We move in the direction of the gradient:

a.data += 0.01 * a.grad

b.data += 0.01 * b.grad

# ... re-run forward pass ...

print(L.data)-7.286496 (increased from -8.0)

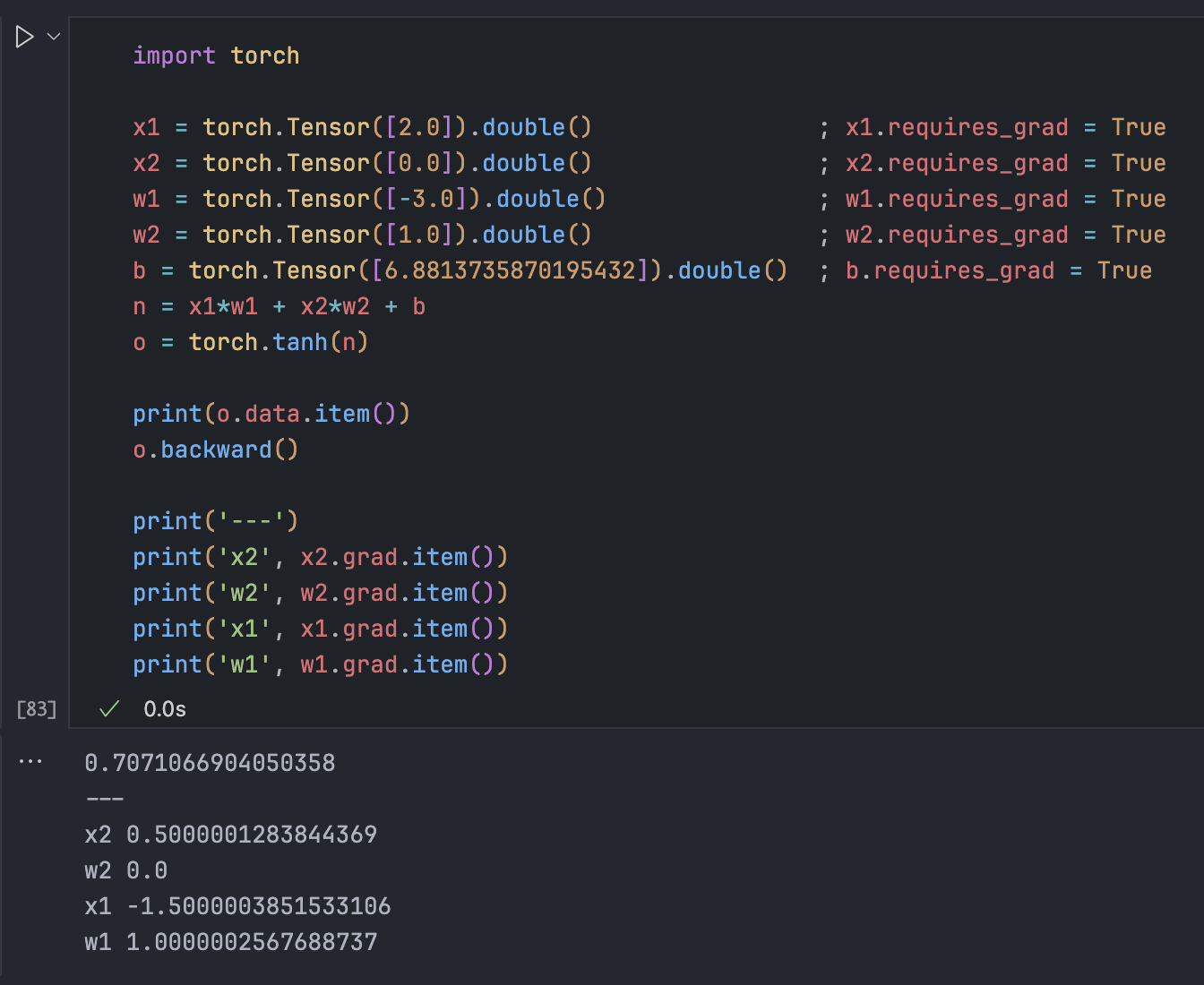

A realistic example:

# inputs x1, x2; weights w1, w2; bias b

# n = x1*w1 + x2*w2 + b

# Activation: o = tanh(n)

def tanh(self):

n = self.data

t = (math.exp(2*n) - 1)/(math.exp(2*n) + 1)

out = Value(t, (self,), 'tanh')

return out

o = n.tanh()

# o.grad = 1.0

# n.grad = do/dn = 1 - tanh(n)^2 = 1 - o^2Derivatives reveal impact. If x2 is 0, changing w2 has zero effect on the output. To increase output, we should increase w1.

Automation

We’ll store a self._backward function in each node to automate the chain rule. We then call these in topological order.

o.grad = 1.0

topo = []

# ... build topological sort ...

for node in reversed(topo):

node._backward()Adding o.backward() to the Value class completes backpropagation for a neuron.

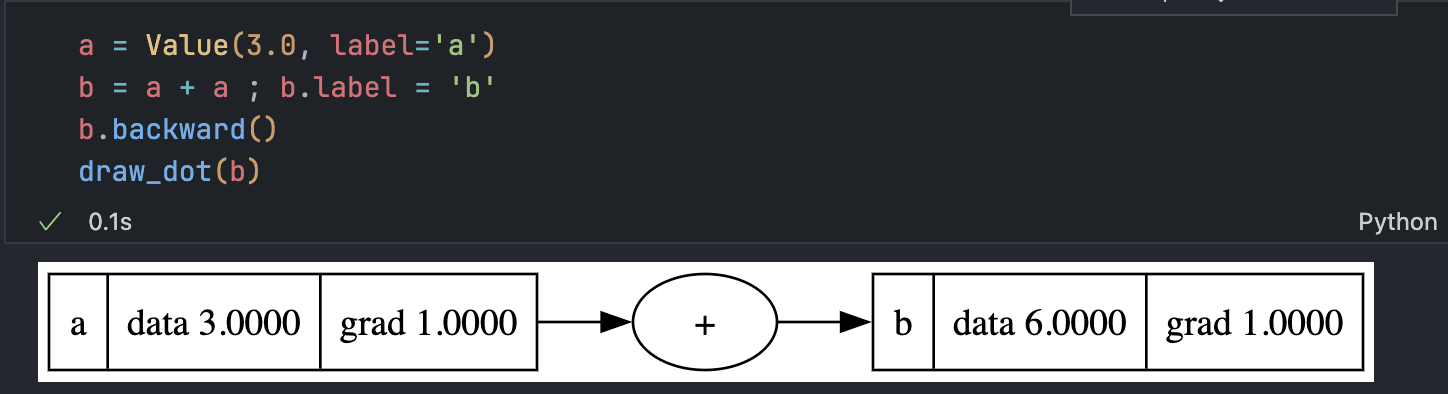

The Accumulation Bug

A serious issue occurs when a node is used multiple times: gradients overwrite each other.

The derivative should be 2, not 1. The fix is to accumulate gradients:

self.grad += 1.0 * out.grad

other.grad += 1.0 * out.grad

Level of Operation

The granularity of the framework is up to you. As long as you can implement the forward and backward pass for an operation, its complexity doesn’t matter.

def tanh(self):

# ... forward pass ...

def _backward():

self.grad += (1 - t**2) * out.grad

out._backward = _backward

return outImplementing all atomic operations:

class Value:

# ...

def __add__(self, other):

other = other if isinstance(other, Value) else Value(other)

out = Value(self.data + other.data, (self, other), '+')

def _backward():

self.grad += out.grad

other.grad += out.grad

out._backward = _backward

return out

def __mul__(self, other):

other = other if isinstance(other, Value) else Value(other)

out = Value(self.data * other.data, (self, other), '*')

def _backward():

self.grad += other.data * out.grad

other.grad += self.data * out.grad

out._backward = _backward

return out

def __pow__(self, other):

assert isinstance(other, (int, float))

out = Value(self.data**other, (self,), f'**{other}')

def _backward():

self.grad += other * (self.data**(other - 1)) * out.grad

out._backward = _backward

return out

# ... sub, radd, rmul, truediv ...Comparison with PyTorch

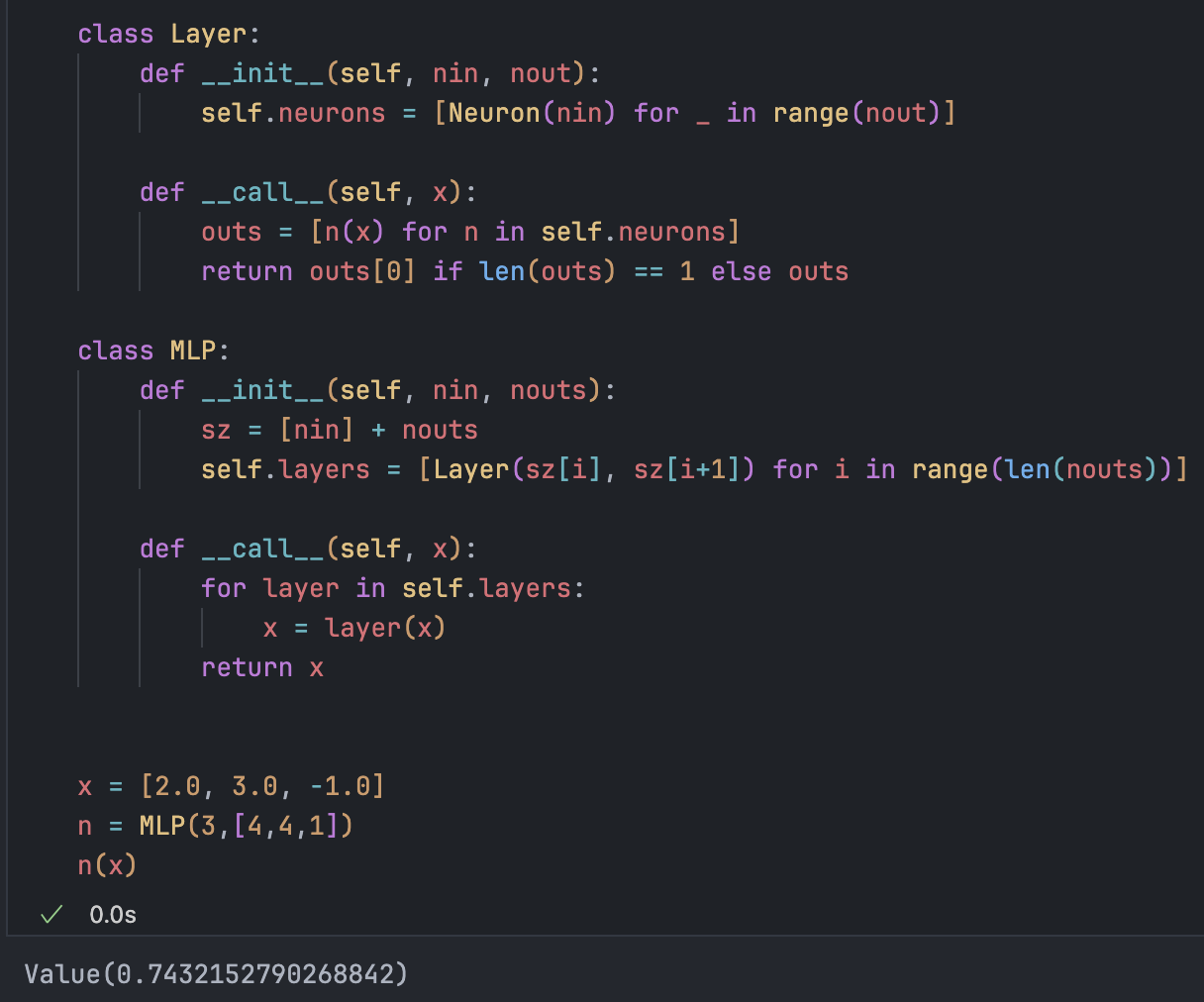

Neuron and MLP Classes

class Neuron:

def __init__(self, nin):

self.w = [Value(random.uniform(-1,1)) for _ in range(nin)]

self.b = Value(random.uniform(-1,1))

def __call__(self, x):

act = sum((wi * xi for wi, xi in zip(self.w, x)), self.b)

return act.tanh()

class Layer:

def __init__(self, nin, nout):

self.neurons = [Neuron(nin) for _ in range(nout)]

def __call__(self, x):

outs = [n(x) for n in self.neurons]

return outs[0] if len(outs) == 1 else outs

class MLP:

def __init__(self, nin, nouts):

sz = [nin] + nouts

self.layers = [Layer(sz[i], sz[i+1]) for i in range(len(nouts))]

def __call__(self, x):

for layer in self.layers:

x = layer(x)

return xImplementing an MLP:

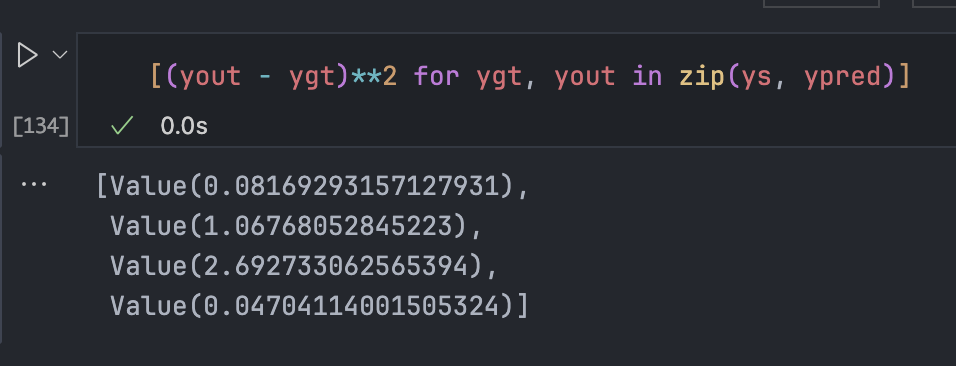

The Loss Function

We measure performance with a single number: Loss. In classical regression, we use Mean Squared Error (MSE).

Total loss is the sum of individual losses.

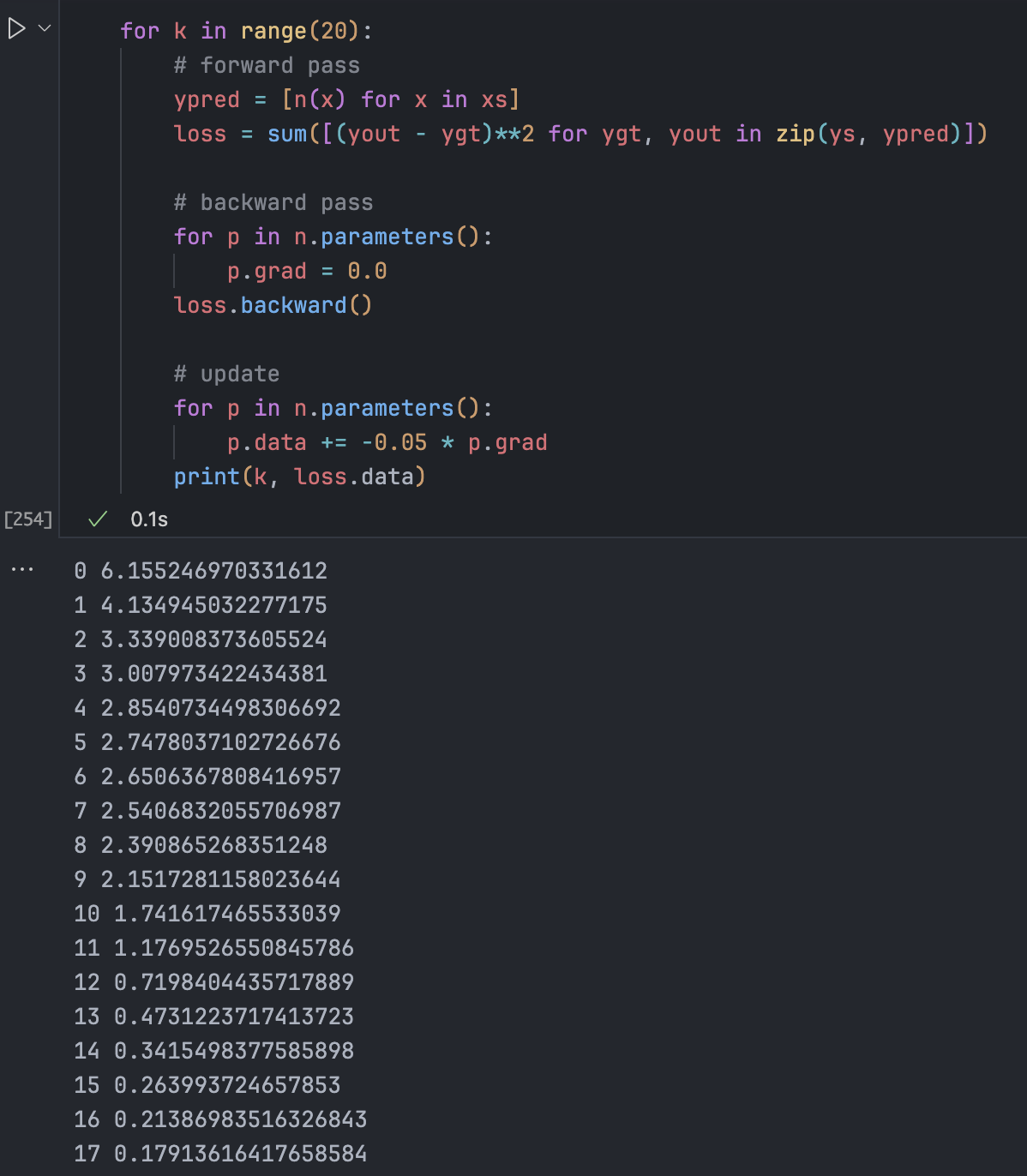

Gradient Descent

Update weights by moving in the negative direction of the gradient:

for p in n.parameters():

p.data += -0.01 * p.gradIteration (Forward pass -> Backward pass -> Update) gradually improves predictions.

Setting learning rates is an art. Too low is slow; too high is unstable (exploding gradients).

Common Issues: Zeroing Gradients

Because our gradients accumulate, we must zero them before each backpropagation. Otherwise, update steps keep growing, causing failure.

Summary: What is a Neural Network?

Neural networks are mathematical expressions. In MLPs, they are relatively simple. They take data and weights as input, perform a forward pass, calculate a loss, backpropagate the loss, and update parameters via gradients to minimize it.

A small network might have 41 parameters; GPT has hundreds of billions. While GPT uses tokenizers and cross-entropy loss, the core principles remain the same.

Learning micrograd reveals the design philosophy behind PyTorch, making it easy to understand how custom functions are registered for automatic differentiation. Official documentation: PyTorch custom autograd functions.